The show makes a compelling case for Bell’s importance as a pioneering 20th-century female artist, even as it illustrates the uneven nature of her work. But Bell also matters, Spira said, “because she democratized a creative practice by paying attention to everything; the domestic, the mundane. It doesn’t sound radical, but it was.”

The Stage Takes Shape for a Trump-Less First G.O.P. Debate

At least eight Republican presidential hopefuls will spar on Wednesday night in Milwaukee, without Donald Trump, the party’s dominant front-runner.

Tracking the roots of money is a daunting, perhaps impossible, task. These books are a good place to start

'Stakeout Diary': A killer on the run, two postwar gumshoes — noir at its finest

When a London-based book dealer happened upon a trove of photos in Tokyo, he sparked an investigation into multiple mysteries that drew international acclaim.

Jimbocho, an area of Tokyo sandwiched between the Kanda River and the Imperial Palace, is a book lover’s dream. Out-of-print novels, vintage cinema posters, essay collections and scholarly tomes line the shelves of its many used bookstores, occasionally spilling out into street carts outside. It’s easy to spend hours strolling its alleys, hunting through the voices from the past.

That hunt is what brought Titus Boeder to the neighborhood one day in the spring of 2004. A London-based dealer in old books who specializes in Far Eastern material, Boeder was perusing what the antiquarian shops had on offer when he happened upon a stack of photographs.

Each measuring 20.3×25.4 centimeters, the monochromatic images depict what look to be a pair of detectives — one perhaps in his 20s, with a well-defined Greek nose; the other, his hair cropped short, carrying the confidence of the senior partner; both wearing trenchcoats over their three-piece suits. They appear to be canvassing working-class neighborhoods in the capital, talking to shop owners, visiting dingy bars and taking drags on cigarettes. The background scenery suggests the shots were captured not too long after the war.

The shopkeeper told Boeder that the images might be stills from a film, and indeed there is something cinematic about them, but Boeder couldn’t help but feel perplexed. If they’d been taken from a movie, he thought to himself, wouldn’t he have seen it? While the detectives carry a kind of effortless cool, the others in the shots — the extras — don’t look like actors at all. There is a strong whiff of realism in the images even though a few of the shots were clearly posed.

Returning to the shop the next day, Boeder purchased all 120 prints and had them sent back home. “When they arrived in London, I had the first chance to look at them carefully,” he says via email. “Every image had an energy within it that was beyond words.”

Some of the photos came packed in an old green Fujifilm cardboard box inscribed with the name of the photographer: Yukichi Watabe.

Although Boeder had been dealing in Japanese photo books from the postwar era for many years — including publications by heavyweights such as Ken Domon and Ihei Kimura — he had never heard of Watabe. That posed another puzzle: Why was this clearly talented photographer not better known?

“I bought books and exhibition catalogs that included his work,” Boeder says, adding that none of this published material had the quality seen in his initial Jimbocho find. Somehow, he says, that style “remained elusive” — Watabe’s other material didn’t have the feeling present in this pile of photographs.

The other mystery was the subject itself. The general outlines were clear: Watabe’s photos depict a police investigation. One of the images includes an office door; the kanji for “satsujin jiken” (murder case) are written on a piece of paper stuck to a doorpost.

“We were dealing with a murder inquiry … but really?” Boeder says. The police would “never allow a photographer to follow an ongoing police investigation. Not in Japan, not anywhere else in the world. Here, we had an almost day-to-day record of police officers looking for clues: Cheap hotels, waiting halls in train stations, small unpaved roads.

“Who, exactly, were they looking for?”

Unearthed by Boeder decades after having been captured through Watabe’s lens, these gritty, noirish photographs of a police investigation in Tokyo would stir interest from around the world and trigger a fresh inquiry into their origins, one that would offer a glimpse into the tumult of 1950s Japan as it labored to rebuild itself from the devastation of World War II.

The body by the lake

Around 3:30 p.m. on Jan. 13, 1958, children looking for fish bait near the southern shore of Lake Senba in Mito, Ibaraki Prefecture, stumbled upon a brand-new oilcan. Inside were a severed left thumb, part of a nose and a penis.

The following morning, eight officers from Mito Police Station and 15 members of the prefectural riot squad split into teams to dredge the lake by boats. Another 30 policemen scoured the surrounding bushes and forests.

Immaculately maintained today, the 1,250-meter-wide Lake Senba adjoins Kairakuen garden, one of the three “great gardens” of Japan. Back then, however, clusters of waist-high weeds sat on its banks, providing plenty of cover for anyone looking for an inconspicuous dumping site.

At around 3 p.m., a severely disfigured male body was found on the opposite side of the lake from where the children had come across the oilcan the previous day. The body was tied up with two pieces of thin string and lay naked on its back in a bamboo thicket. The dismembered parts from the oilcan appeared to have been taken from the corpse.

The entire body had been doused with sulfuric acid, the face and fingertips were particularly burned. The victim’s head was also carved up with a razor; there were approximately 30 lacerations zigzagging up and down the face. In addition, the papillary ridges on the fingertips were mutilated, likely in an effort to prevent the individual from being identified.

Aside from the body and the oilcan, the only item left behind was a hand towel from a ryokan (traditional inn), which searchers collected from a public restroom 30 meters from where the body was found.

An autopsy revealed the cause of death to be strangulation; and the estimated time put between 5 p.m. and 9 p.m. on Jan. 12. The victim was thought to have been between the ages of 25 and 35.

A special task force convened, and a print of the severed thumb was taken. It matched with Tadashi Sato, 29, a day laborer from Tokyo’s Sumida Ward who had a record of being arrested by officers from Ueno Police Station for auto theft.

Police spoke with Sato’s family, who said that, around noon on Jan. 9, he had brought home a man named “Nishida” who claimed to own a leather shop in Gifu Prefecture, around 270 kilometers west of the capital.

Nishida said he was recruiting Sato as a salesman for his business, and asked for Sato’s change-of-address certificate and a copy of his family register. He returned the following day, retrieved the documents and took Sato away with him.

As the police investigation proceeded, the hand towel led officers to the Yoneya ryokan in Asakusa, Tokyo’s leading entertainment district at the time. The inn’s ledger showed the names of Sato, as well as a certain Tamotsu Nishida, 30, of Hozumi, Gifu Prefecture. Their appearances and other details matched, leading investigators to presume that Nishida had murdered Sato.

The question was, why?

“Then came the hard part,” said the late Tsuyoshi Hanawa in a chapter he dictated in a 1980 book, “True Crime in Ibaraki: A Quarter Century of Testimony by Prefectural Police Investigators.”

“After all, the scene had moved to Tokyo,” said Hanawa, who was a chief inspector with the Ibaraki Police at the time of the investigation. “For a time, we were in the dark about how to operate in the jungles of Tokyo.”

The man behind the lens

Half a century after the crime, Boeder was in the middle of his own investigation, poring over Watabe’s photographs with the aid of a Japanese friend trying to uncover the context of the work.

They discovered a clue that led to a breakthrough: One of the images showed a pile of freshly printed arrest warrants inside a police station. The warrant atop the pile had the name “Tamotsu Nishida” written in the top right corner.

“This took us to a website that gave details of serial killings in Japan,” Boeder says. “Suddenly, we had the full picture. It seemed like a miracle. Yes, the police had allowed Watabe to make a record of an ongoing investigation.”

Boeder put the photos up for sale, offering this description of the trove:

Watabe follows a police investigator as he interviews workers at a tannery, shoe-makers, pawn-shops, neighborhood cops, hotel owners and others. … During this process, Watabe records much more than just the policeman and his investigation — he shows a point in the history of Tokyo that is rarely seen. He does so with the eyes of a professional of the highest order, framing, posing, manipulating in a manner reminiscent of film noir. … Watabe clearly feels the rush of excitement with an opportunity that he knows will never return.

In 2009, Boeder sold Watabe’s prints to an American collector.

Two years later, the collection was compiled into a photo book by French publisher Editions Xavier Barral under the title, “A Criminal Investigation.”

It became an international bestseller, appearing on lists of top photo books that year, including Time magazine’s “Best of 2011.” In a 2012 Daily Telegraph article, fashion designer Paul Smith lists the collection as one of his top 10 favorite books of all time.

So, case closed? Not quite. While the book garnered a dedicated following at the time, there was still the matter of the identity of its two protagonists: the cool detectives who had enchanted artists and designers alike. And how did Watabe, a freelance photographer, manage to gain such rare access to a homicide investigation?

Yukichi Watabe was born on Feb. 18, 1924, in Sakata, Yamagata Prefecture — a city in northeastern Japan that sits on the Sea of Japan coast. Known as a thriving transit port for merchants during the Edo Period (1603-1868), it was also the birthplace of Ken Domon, 14 years Watabe’s senior and one of Japan’s most acclaimed photographers.

Watabe’s career began in 1943, after he joined a photo studio in the capital called Tokyo Kogasha. He was summoned for military duty in 1945, and served as an army photographer until the end of the war that year.

In the postwar years, he worked as an assistant to Shigeru Tamura, a notable photographer in the fields of fashion and photojournalism who was known for, among other things, shooting what might be the most famous portrait of novelist Osamu Dazai.

Watabe struck out on his own as a freelancer in 1950 and began submitting photographs to respected monthly magazines including Chuo Koron and Bungei Shunju. It was during this period that he was commissioned by Nihon, a now-defunct magazine published by Kodansha, to accompany two detectives on a murder investigation.

It was 13 years after Japan’s World War II surrender. The nation was in the middle of sweeping, unprecedented socioeconomic change: Its military had been disarmed, the government democratized and the education system reorganized. Massive infrastructure projects were undertaken to rebuild cities ravaged by Allied air raids, including the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

The economy took off as the manufacturing sector roared back into action. Sustained prosperity and robust annual growth rates accelerated rural-to-urban migration, crowding big cities like Tokyo with those who left the countryside in search of employment. The entertainment industry flourished, and red-light districts proliferated in response to the influx of migrant workers.

The postwar years also saw many people disappear without a trace — there were more than 85,000 such cases recorded in 1958 alone. Oftentimes, these were people purposefully severing contact with their families and social circles for one reason or another: to escape an abusive family or difficult breakup, or to simply cut ties with the past in a new era of possibility.

A majority of the disappeared would eventually reappear, but occasionally the missing would never resurface. Perhaps they remained hidden due to the shame of not making it in the city, or fell victim to malicious schemes that led to financial ruin, criminal associations or murder.

‘It’s a nasty business’

It’s unclear how the editors at Nihon negotiated the deal with the police, but Watabe was given the green light to spend 20 days with a pair of inspectors as they questioned witnesses and wandered the dusty streets of Tokyo in search of a killer.

This likely took place in March 1958, two months after the discovery of the body by Lake Senba and, as we will later learn, right after the detectives in question returned from Gifu, where they had spent a month tracing the footsteps of Nishida, their suspect, to no avail.

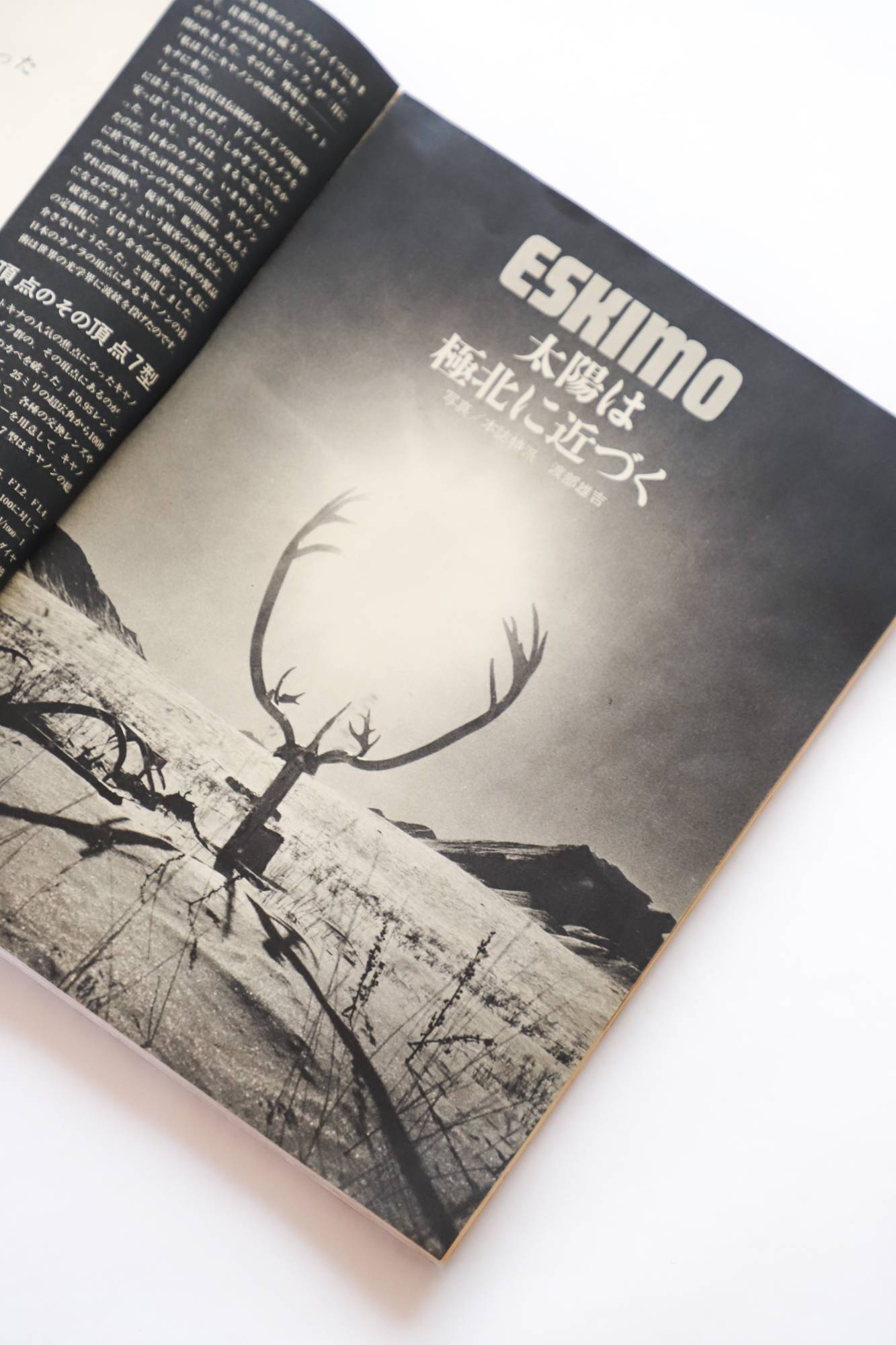

Tokyo at that time is described in one of the captions for a selection of Watabe’s photographs published in the June 1958 issue of Nihon under the title, “Harikomi Nikki” (“Stakeout Diary”):

It may feel too small for those on the run, but the city is too big for those in pursuit. My colleagues and I continue our legwork today. The steam whistle responds to our empty bellies, and dusk is approaching the overpass at Ueno.

The captions read like hard-boiled fiction, switching back and forth between first person and third person, and sprinkled with police jargon. The images are sequenced to reconstruct the footsteps of the detectives, who are never given names. In fact, readers aren’t let in on many of the details of the case they’re investigating, which may well have been part of the arrangement between Nihon and the police in the first place.

Another caption:

Are there any signs of lives in disarray among the throngs of people flowing through the streets? Or the shadows of desperation? That is where the seeds of crime are. I am a detective, on the hunt for that look of gloom. “It’s a nasty business,” people say.

The dozen photographs that made it into the magazine are intriguing. However, the busy layout (made even busier with advertisements for Japanese whisky and, yes, cameras) takes away from the dark, nuanced ambience the images convey.

When Boeder saw them 46 years later without all the noise and cropping, without any indication of when and where they had been filmed, their true appeal stood out.

In any case, by all indications Watabe saw this as just another passing project as he worked to cement his own place in the world of photography.

In the fall of 1960, he departed on his first overseas trip, spending a total of eight months in Africa and Europe — an experience that would hook him on world travel. “I still remember how much fun I had on that first trip,” he wrote in “All About Overseas Travel Photography,” a book he published in 1978.

Following his return from that first trip, he flew to Alaska to photograph indigenous people over a three month-period for the first issue of the monthly magazine Taiyo (The Sun). Published in 1963, the acclaimed magazine’s inaugural issue includes a picture of Watabe, then in his late 30s, posing in Alaska for an advertisement for Pentax cameras. The magazine also featured photos by none other than Ken Domon.

Watabe continued to fly around the globe over the following decades, releasing a spate of photo books including “The Great Egypt” (1973) and “Morocco” (1994). He also spent many years documenting kagura, a type of Shinto ceremonial dance, an effort that culminated in the award-winning “Kagura,” published in 1989.

In 1992, he received the Medal with Purple Ribbon from the emperor in recognition of his achievements in the fields of art and academia. He died Aug. 8, 1993, at the age of 69.

While respected among the Japanese photography community, he never achieved the level of success some of his contemporaries had enjoyed.

At least, not until “A Criminal Investigation” was published two decades after his death.

A modern mystery

While “A Criminal Investigation” was receiving rave reviews outside of Japan, the identity of the two police officers remained unknown. Things soon began moving, however, when nonfiction writer Tsuneyoshi Noji visited Paris for research in 2012.

Stepping into Le Bal, an exhibition center dedicated to contemporary images, he found copies of the Watabe volume on display. Canvas-covered and carefully bound, the compilation itself was a work of art, embellished by old-school typewriter texts and an elastic strap reminiscent of a detective’s notebook.

“Noji happened to know Takaji Kunimatsu, the former chief of the National Police Agency — they would go out for meals,” Yoji Kako, a senior staff writer at the Tokyo Shimbun daily, says from the lobby of the newspaper’s building near Tokyo’s bureaucratic heart of Kasumigaseki. “Thinking it would be a fun souvenir, Noji bought a copy each for himself and Kunimatsu and took them back home to Japan.”

A veteran journalist, Kako writes a monthly column in which he explores the story behind a single photograph. For his June 2022 column, he examined the mystery behind Watabe’s collection.

“Kunimatsu was delighted with the gift, and asked the Tokyo Metropolitan Police Department’s chief of criminal investigations to find out who the cops in the photos were,” Kako says. “Who could refuse? These were orders coming from the big boss himself.”

Kako had been on the police beat as a young reporter and understood how difficult it was to follow and report on an ongoing investigation.

“I was in awe at how close Watabe had gotten to the cops,” he says. “There was also something very raw about the photographs. You could sense the detectives had relaxed their guards around Watabe — it was as if they didn’t notice he was there.”

In the summer of 2011, prior to Noji’s gifting of the volume to Kunimatsu, photo book collector Atsushi Saito asked a fellow hobbyist in the U.K. to pass along some new recommendations. Watabe’s name was floated, and Saito ordered a copy of “A Criminal Investigation.”

“I assumed Watabe was a young, up-and-coming photographer,” Saito says during a chat at a cafe next to the Tokyo Photographic Art Museum in Meguro Ward. “So I was startled to see images that appeared to be from the early Showa Era (1926-89).”

‘Stakeout Diary’

Bespectacled and soft-spoken, Saito is an amateur photographer with a keen eye for diamonds in the rough. While it may be hard to imagine from his subdued demeanor, he used to be a weekend club DJ going by the name “Roshin,” spinning gabber, a subgenre of hardcore techno born in the Netherlands.

Captivated by Watabe’s dark, evocative images, Saito decided to contact the photographer’s surviving family members. He got in touch with his son, Hiroyuki Watabe, in November 2011. Hiroyuki agreed to a loan of his father’s negatives from the 1958 shoot.

There were far more shots from those 20 days than he’d expected: In all, 32 24-exposure rolls. Using the material, Saito hosted an exhibition the following June in Kiyosumi Shirakawa, an old neighborhood in eastern Tokyo known for art galleries and coffee shops.

A few days after the event wrapped up, an officer from the Metropolitan Police Department called the gallery and told Saito they were trying to locate the officers in the photos. Although Saito didn’t have any useful information to share, the police promised to update him regarding any developments.

Soon Saito received a call from the son of one of the detectives. This was the eldest son of the senior investigator in the images, who now had a name: Tsutomu Mukaida, a career police officer who had been 42 years old at the time of the Lake Senba murder investigation. The identity of his youthful sidekick remained unclear.

Mukaida’s son, who had recently been contacted by police about his father, offered an important lead. He said he recalled that the younger detective worked for the Ibaraki Police.

His curiosity aroused, Saito phoned the Ibaraki police headquarters and explained the situation. To his surprise, he received a call from the younger detective himself.

Saito drove up to see the man, Katsumi Midorikawa, who had retired and was living in Kasama, a mid-sized city in central Ibaraki Prefecture.

“It was a strange feeling because the young man in the photo, whose face I had stared at during the entire exhibition, appeared in front of me as an old man nearing his 80s,” Saito wrote in a blog post following his encounter in 2012.

Sprightly for his age, Midorikawa had a clear memory of the events that had unfolded during that winter. He told Saito of the discovery of the oilcan and the body; how the grisly murder threw the Ibaraki police into confusion; how he and other cops were dispatched to the metropolitan police department to hunt down the suspect.

Unfamiliar with the capital’s labyrinthine backstreets and alleys, the police decided to pair Midorikawa, then 25, with Mukaida, who was known as one of the best detectives in the metropolitan police’s first investigation division.

The two spent the whole of February 1958 in Gifu Prefecture, tracing the address Nishida left in the ryokan ledger. His home address and name were fabricated — the investigation turned up nothing. Upon their return to Tokyo, Watabe joined them with his camera, immortalizing their search.

With his exhibition a success, Saito was hoping a publisher would be interested in releasing Watabe’s work in Japan, where it remained obscure. “But no one raised their hand, so instead I launched my own publishing outfit.”

He called it Roshin Books, in a nod to his old DJ name, and the first edition of the collection, titled “Stakeout Diary,” was published in 2013. In response to popular demand, a second edition was released the following year. Both sold out.

Meanwhile, Saito reached out to the independent publisher Nana Roku Sha, who agreed to release a cheaper, paperback edition of “Stakeout Diary” in 2014. “I couldn’t publish in mass quantities, so I wanted a popular edition out there,” Saito says.

And this year, in commemoration of the 10th anniversary of his founding of Roshin Books, Saito published 800 copies of the third edition — a black, hard-covered beauty running at 104 pages. “I just want to help Watabe’s work get noticed,” he says.

During that decade, however, both Midorikawa and Hiroaki, Watabe’s son, passed away. The number of those left to tell the story of the peculiar trio was dwindling.

Japan’s most wanted

Despite Mukaida and Midorikawa’s efforts, the killer remained at large and the case was getting cold.

On July 9, 1958, six months after the Lake Senba murder, the National Police Agency — in a first attempt of its kind — issued a wanted list for 21 murders and robberies nationwide, involving a total of 26 suspects whose photographs were printed and posted on bulletin boards across the country.

Among them was Katsumi Onishi, 30, wanted for the 1955 murders of his adoptive parents in Shimonoseki, a city in Japan’s western Yamaguchi Prefecture.

Born in 1927, Onishi’s biological parents parted ways before his birth. He was raised by Kuma Onishi and her husband, Fukumatsu. Court records indicate young Katsumi had a troubled childhood; the Onishis were heavy drinkers and showed little affection toward their children.

In 1947, Onishi was sentenced to seven years for home invasion and robbery and to 18 months for theft. He served the sentences until 1951, when he was released on parole. He found a job and, in 1953, married a coworker. With his new wife he moved back into the home of his adoptive parents.

Things didn’t go well. Fukumatsu would binge-drink while Kuma hurled abuse at Onishi’s pregnant wife, ordering her son to divorce her. Household finances were deep in the red, and Onishi began embezzling money from his workplace to pay for his parents’ spendthrift outlays on booze, other entertainment expenses and new appliances. “No matter how much I asked my parents to reform their characters, it didn’t work,” he said in a 1960 supreme court appeal against his death sentence.

Following a heated argument one night in early June of 1955, Onishi killed Kuma and Fukumatsu by mixing cyanide into their beverages. He considered taking his own life as well, but got cold feet and went on the run instead, hopping across prefectural lines and picking up odd jobs here and there under a different name.

An increasingly paranoid fugitive, he began obsessing over stealing someone’s identity, and headed to Tokyo in early 1956. Several days after arriving in the capital, befriending a man around the same age named Akio Miura, Onishi boasted that his father operated a Nagoya-based shipping firm.

He offered Miura work in return for a copy of his family register and change-of-address certificate. The two traveled west, and Onishi poisoned Miura in the mountains of Kurashiki, Okayama Prefecture, by mixing cyanide into a digestive medicine he offered. He burned Miura’s body with eight liters of gasoline, and promptly assumed his identity.

A crucial mistake he made in December 1957, however, would lead to his arrest. Heavily intoxicated one night in the capital, Onishi entered a house and was caught and held by the police for theft. Although he later was released, he had been photographed and fingerprinted during his interrogation.

By then, he was working and newly married to a pregnant wife, all under the Miura alias. Onishi panicked. His fingerprints were a liability.

He needed another identity, fast, and set his sights on Tadashi Sato, whom he would strangle to death by Lake Senba less than a month later. His plan to take over Sato’s identity failed, however, when the children’s discovery of the oilcan led officers to find Sato’s body.

On July 15, 1958, a week after the police released their nationwide wanted list, Onishi was arrested.

Investigators reviewing his fingerprints discovered they matched those of a man named Akio Miura of Tokyo’s Meguro Ward. They visited the apartment on the address, and Onishi confessed to killing his parents and, later, to the murders of both Miura and Sato.

“I do not mean to speak ill of the dead, but if the defendant’s adoptive parents had treated him with the same love and affection as the rest of us know, such a tragic outcome would never have occurred,” his lawyer, Kiyosaku Sato, said in the 1960 appeal.

Onishi was hanged in 1965.

The ephemeral metropolis

Tokyo, as I’ve come to understand it, is a city stuck in a perpetual cycle of demolition and rebuilding, its landscape changing by the day.

Much of the scenery Watabe captured during those three weeks in 1958 has disappeared. Tin-roofed shacks and nagaya tenements; the tiny print shops; the kimono-clad shopkeepers — all now faint memories of a fading past.

Hidden behind the glassy high-rises and bustling shopping streets, however, are the musty remnants of red-light districts and smoky alleyway bars that preserve traces to the city’s history.

Ueno, the commercial neighborhood in the east of the capital whose streets detectives Mukaida and Midorikawa and photographer Watabe roamed, still hangs onto its black-market origins with cheap izakaya pubs, clothing stores and fresh-food vendors packed under the rumbling train tracks.

Asakusa, where Onishi spent a night at the Yoneya ryokan with his final victim, Sato, retains some of its past character with its temples, retro coffee shops and open-air bar streets filled with horse-racing fans.

On a crisp, winter morning earlier this year, I got off the train at Sugamo, a district in Toshima Ward known as the “Granny’s Harajuku” for its 800-meter-long Jizo Dori shopping street catering to seniors.

Most of the stores were yet to open as I made my way down the street toward the residence of Masatoshi Mukaida, the eldest son of Tsutomu Mukaida.

After a long day trudging through the city, detective Mukaida would head back here to Sugamo to unwind with his wife and three sons, cigarette smoke wafting through the tatami-floored room as he lay on his side and contemplated the progress of his investigation.

“This area was basically just an open field back then,” Masatoshi tells me after he and his wife, Kyoko, serve me tea in their living room. The couple now live with their son, daughter-in-law and grandchildren in a modern, two-family home they built on the property some years ago.

Masatoshi’s resemblance to his father is striking. They share the same upside-down, U-shaped eyebrows, strong jaw and protruding cheekbones. And physical likeness is not all. Now retired, Masatoshi was also a career police officer. At 78, however, he is now 20 years older than the age at which his father died from cirrhosis of the liver.

Although the disease is often associated with alcohol abuse, Mukaida — never mind the hard-boiled image conjured from Watabe’s photographs — didn’t drink. Instead, his hobby was studying, performing and teaching classical Japanese dance, a style known as Nihon buyō more specifically. He was hoping to spend his time as an instructor of the art after retiring at 55, Masatoshi says.

Like Watabe, Tsutomu Mukaida, better known as “Riki” among his neighbors and friends, was born in Yamagata Prefecture — and perhaps this was one reason the two appeared to have developed a kinship during the shoot. Masatoshi recalls Riki as a gentle yet workaholic father who was always ready on call. Family outings were rare.

“There were many days he wouldn’t come home from work,” Masatoshi says. Just once they went to Atami, a seaside hot-spring resort in neighboring Kanagawa Prefecture, for an overnight family trip, “but he got a call once we arrived and had to do a U-turn back to the investigation headquarters.”

The senior Mukaida excelled at his job as a criminal investigator, receiving close to 200 awards during his life. “He was delighted to learn that I wanted to become a police officer,” Masatoshi says, “but I hated being compared with him — so much so that when I joined the police I transferred to the traffic and riot police units.”

Masatoshi has seen his own share of historical events during his career. He was deployed to contain rioters during the student movements of the 1960s and ’70s. He was dispatched to the Asama Sanso mountain lodge during a hostage crisis — broadcast live on television — involving members of the United Red Army in 1972. More recently, he was among the riot police on the scene of the 1995 sarin gas attacks in Tokyo by doomsday cult Aum Shinrikyo.

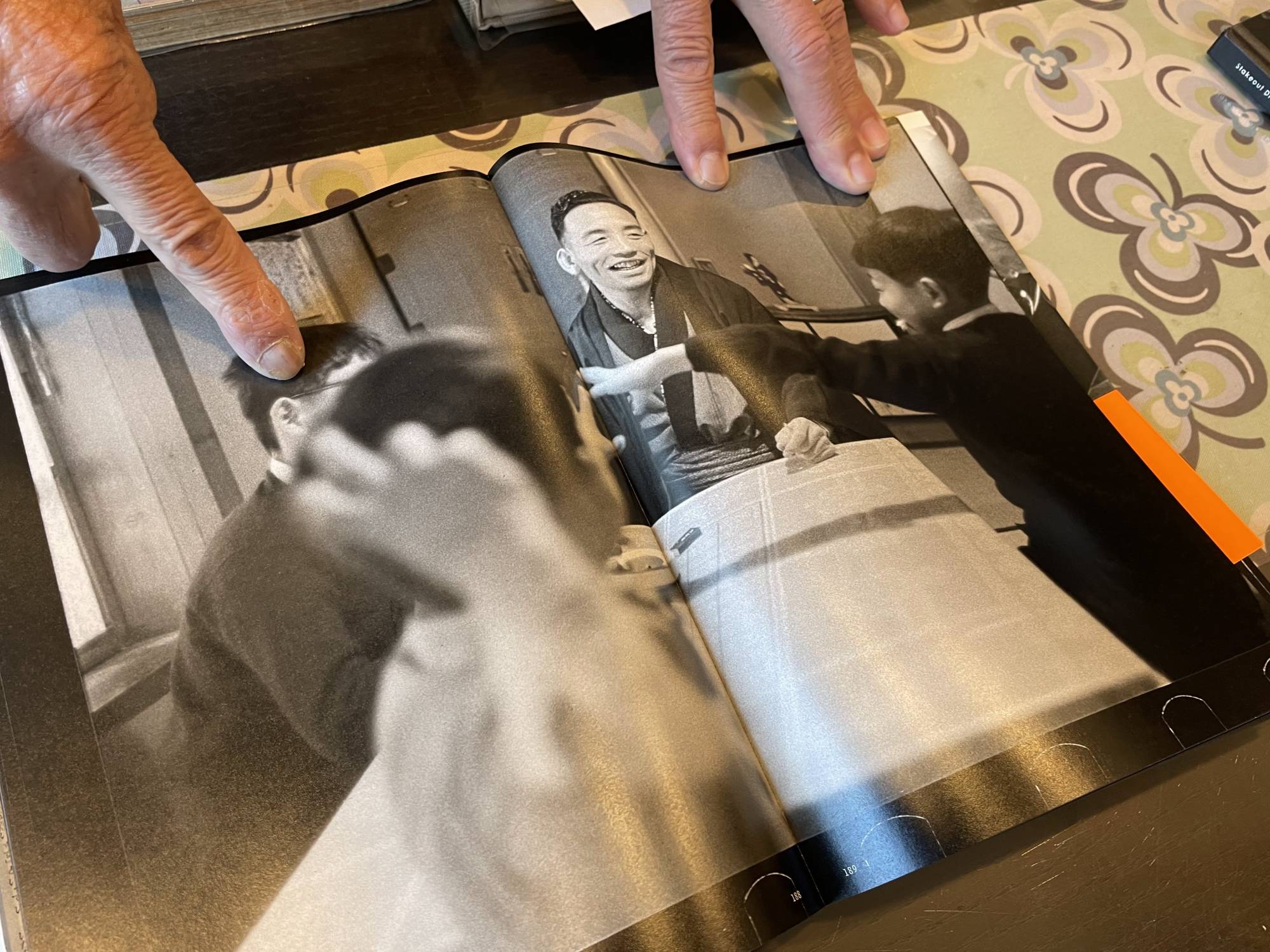

Flipping through a copy of “Stakeout Diary” that I brought along, Masatoshi points to an image showing his father, relaxed and grinning at his home, sitting on the far end of a rectangular table and surrounded by his three sons. “This boy on the left, wearing glasses. That’s me,” he says, “but for some reason I don’t recall Mr. Watabe visiting our place.”

For Masatoshi, the events of the past decade were a strange turn of fate. He had no idea that his father’s images were circulating overseas, and didn’t know that various parties were out looking for clues to his father’s identity.

All the attention has brought back memories, though. “Just 10 days before you called, my brothers and I went on a trip and visited Lake Senba,” Masatoshi tells me. “I knew it was where the murder had taken place, and wanted to take a look. But it’s all cleaned up and nothing like how it was in the photographs anymore.”

Taking the box of Japanese traditional sweets I’d brought as a souvenir to the butsudan, or Buddhist altar in the corner of the room where his parents and ancestors are enshrined, Masatoshi joins his palms together and bows in silence for a few seconds.

The last image in Roshin Books’ edition of “Stakeout Diary” is a shot from behind of detectives Mukaida and Midorikawa walking along train tracks, their trench coats flapping in the wind. We don’t know where they’re headed, but their footsteps seem firm as they navigate the changing contours of the city.

Later in the year those photos were taken and five months after Onishi’s arrest, a symbol of Japan’s postwar recovery would be completed: Tokyo Tower, a 333-meter orange giant in the center of the capital that lights up every night.

Today, the Mukaida family’s police legacy continues. “I’ve actually never told outsiders about this before,” Masatoshi says as I prepare to leave.

“My son is also a cop. He says he’s going to follow in his grandfather’s footsteps.”

沒有留言:

張貼留言