COLLOTYPE膠版

Collotype is a gelatin-based photographic printing process invented by Alphonse Poitevin in 1855 to print images in a wide variety of tones without the need for halftone screens.[1][2] The majority of collotypes were produced between the 1870s and 1920s.[3] It was the first form of photolithography.[4]

Invention

[edit]

Collotype originates from the Greek word kolla for (flour paste) glue.[5] Poitevin patented collotype printing the same year it was invented in 1855. The process was shown in 1859 by F. Joubert.

Process

[edit]Poitevin's Collotype

[edit]In Poitevin's process, a lithographic stone was coated with a light-sensitive gelatin solution and exposed through a photographic negative.[6][7] The gelatin would harden in exposed areas, leading to the stone becoming hydrophobic in light areas (and thus receptive to the greasy ink) and hydrophilic under dark areas (ink-repelling).[5][6] The stone was then printed via the standard lithographic process, producing a monochrome print.

1860s Developments

[edit]In 1865, Tessie du Motay and C. R. Marechal applied the gelatin to a copper plate, which was easier to handle than a lithographic stone.[5] However, the gelatin did not adhere well and limited print runs to about 100.[5]

In 1868, Joseph Albert and Jakub Husník applied a gelatin-albumen mixture to glass, which was then coated with light-sensitized gelatin.[5] This allowed print runs of up to 1,000.[5] This patent was later purchased by Edward Bierstadt, who developed one of the first commercial collotype companies in New York City.[8]

Later collotype

[edit]The collotype plate is made by coating a plate of glass or metal with a substrate composed of gelatin or other colloid and hardening it. Then it is coated with a thick coat of dichromated gelatin and dried carefully at a controlled temperature (a little over 50° Celsius) so it "reticulates" or breaks up into a finely grained pattern when washed later in approximately 16 °C water. The plate is then exposed in contact with the negative using an ultraviolet (UV) source which changes the ability of the exposed gelatin to absorb water later. The plate is developed by carefully washing out the dichromate salt and dried without heat. The plate is left in a cool dry place to cure for 24 hours before using it to print.

Related processes, or processes developed from collotype, or even alternate names for collotype include albertype, alethetype, autocopyist, artotype, gelatinotypy, heliotype, hydrotype, indotint, ink-photo, leimtype, lichtdruck, papryrotype, photogelatin, photophane, phototype, Roto-Collotype, Rye's, and Sinop.[9][5][10][4]

Color collotype or chromocollotype

[edit]In 1874, Joseph Albert produced the first color collotypes with three collotype plates, each inked in a different color.[5] In 1882, the Hoeschtype, which used six plates, was patented.[5]

Combination processes

[edit]

Mezzograph collotype

[edit]Mezzograph was a trade name used by Valentine Co. Ltd. of Scotland, for their multicolored postcards, printed in a hybrid process where colors were printed via photolithography and then overprinted in black or blue collotype for the "outlines" of the image.[5]

Halftone collotype

[edit]Halftone collotype processes combine halftone printing and collotype. These include the Jaffetype, developed in Vienna; the Aquatone, developed and patented by Robert John in the United States in 1922, in which the gelatin is not reticulated;[11] the Gelatone process, introduced in 1939; and the Optak process, introduced in 1946.[5]

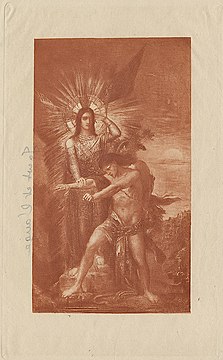

Characteristics

[edit]Collotype was most often printed in monochrome in various colors of ink, most commonly black, brown, green, blue.[12] In double-rolled collotype, the plate was first inked with stiff black ink and then re-inked with a softer colored ink; only one impression was taken.[13] This process was most common in fancy postcards.[13]

Collotype has a finely reticulated pattern that captures the tonal shifts of photography with a much more subtle effect that other photographic printing processes of the late 19th century, such as halftone engraving.[4] Under magnification, the edges of the print appear as diffuse fine curved lines, unlike the more defined edges of relief or intaglio prints.[14]

Richard Benson has described the finnicky nature of collotype printing, primarily problems of registration with damp paper and the varied tones from sheet to sheet.[12] As a young printer during the 1960s, Benson recalled how superstitious the collotype printers were because of the delicacy of the process.[12]

As collotype is a hand-printed process, it can be printed on hand-made paper, which differentiates it from other forms of photographic reproduction.[15]

沒有留言:

張貼留言