syria dispatch

A Tour of Assad’s Monumental Palace, With a Scruffy Rebel as a Guide

The televisions may be stripped away now, but a presidential residence still contains many remnants of a brutal reign.

In 1981, the Japanese Ministry of International Trade and Industry set aside $850 million for the Fifth generation computer project. Their objectives were to write programs and build machines that could carry on conversations, translate languages, interpret pictures, and reason like human beings.[167] Much to the chagrin of scruffies, they chose Prolog as the primary computer language for the project.[168]

The story of chintz is “a tale of armed trade, colonialism, slavery, and the dispossession of native peoples”.

« Mon meilleur ouvrage c'est toi, mon cher enfant ! » ~Alexandre Dumas Père

「我最好的作品就是你,我親愛的孩子!」~大仲馬

wiki:

1852年小仲馬的話劇《茶花女》初演時,大仲馬正在布魯塞爾過著短期的流亡生涯,小仲馬給他電報上說:「第一天上演時的盛況,足以令人誤以為是您的作品。」大仲馬回電說:「我最好的作品就是你,我親愛的孩子!」。

How authors from Dickens to Dr Seuss invented the words we use every day

The English language didn't just spring from nowhere. So who introduced such gems as cojones, meme, nerd and butterfingers?

Paul Dickson

The Guardian, Tuesday 17 June 2014 19.00 BST

Wordsmiths: Charles Dickens, George Eliot, Dorothy Parker and Ernest Hemingway are all the surprising sources of some of our everyday words. Photograph: Getty Images/Alamy/Sportsphoto Ltd - Allstar/Guardian montage

Butterfingers

Charles Dickens used the term in his 1836 The Pickwick Papers (more properly called The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club): "At every bad attempt at a catch, and every failure to stop the ball, he launched his personal displeasure at the head of the devoted individual in such denunciations as 'Ah, ah!—stupid'—'Now, butter-fingers'—'Muff'— 'Humbug'—and so forth."

INFORMAL

A clumsy person, especially one who fails to hold a catch.

The result: timeless songs full of jangling guitars and giggling vocals and lyrics about being a lovesick butterfingers in a world of emotional icebergs.

But the butterfingers company boss Jerry Sanders later let them slip through his fingers.

Unfortunately I'm a butterfingers and grabbed the door latch when I got a hold and the door swung open, with me on it.

HANAMI, or cherry-blossom viewing, is jokingly referred to as the most popular spectator sport in Japan. In truth, the title belongs to baseball.

But “spectator” is a misnomer, because attending a baseball game in Japan involves active, enthusiastic participation.

misnomer

noun [C]

a name that does not suit what it refers to, or the use of such a name:

It was the scruffiest place I've ever stayed in, so 'Hotel Royal' was a bit of a misnomer.

It's something of a misnomer to refer to these inexperienced boys as soldiers.

unbecoming

Pronunciation: /ʌnbɪˈkʌmɪŋ/

ADJECTIVE

1(Especially of clothing or a colour) not flattering:a stout lady in an unbecoming striped sundress

MORE EXAMPLE SENTENCESSYNONYMS

2(Of behaviour) not fitting or appropriate; unseemly:it was unbecoming for a university to do anything so crass as advertising its wares

chintz の定義

名詞

1

printed multicolored cotton fabric with a glazed finish, used especially for curtains and upholstery.

Chintzy

Originally this word meant to be decorated or covered with chintz, a calico print from India, or suggestive of a pattern in chintz. It was extended to mean unfashionable, cheap or stingy, coming from none other than Mary Ann Evans, better known by her pen name George Eliot, who wrote in a letter in 1851: "The effect is chintzy and would be unbecoming."

chintzy

Chortle

Blend of "chuckle" and "snort", created by Lewis Carroll in Through the Looking-Glass: "'O frabjous day! Callooh! Callay!' He chortled in his joy." Carroll also coined the term "portmanteau word", for merging two existing words into one new word. In such blending, parts of two familiar words are yoked together (usually the first part of one word and the second part of the other) to produce a word that conveys the meanings and sound of the old ones – smog from "smoke" + "fog", and brunch from "breakfast" + "lunch". Portmanteau itself is a quaint word for suitcase, originally combining the French porter (to carry) and manteau (cloak) to make a name for a cloak-transporting suitcase designed for carrying on horseback. Lexicographer Ben Zimmer has noted that the portmanteau "remains perhaps the most popular method of new word formation in English, from slang ('chillax', 'geektastic') to business jargon ('webinar,' 'advertorial')".

Cojones

Testicles in the allegorical sense, representing courage and tenacity. Imported from Spanish by Ernest Hemingway in his 1932 nonfiction bullfighting opus Death in the Afternoon: "It takes more cojones," he wrote, "to be a sportsman where death is a closer party to the game."

cojones

Line breaks: co|jo¦nes

Pronunciation: /kəˈhəʊneɪz/

NOUN

Debunk

A word created by the novelist, biographer and former advertising copywriter William E Woodward for the process of exposing false claims. He used it in his 1923 novel Bunk, in which he also created the term debunker and debunking. Others would later debunk Woodward's biographies of George Washington and Ulysses S Grant, which attempted to debunk great figures of history but were generally dismissed as exercises in cynicism and little else.

Doormat

As a metaphor applied to a person upon whom other people "wipe their boots". First used in this sense by Dickens in Great Expectations: "She asked me and Joe whether we supposed she was door-mats under our feet, and how we dared to use her so."

Eyesore

William Shakespeare coined this word for something that is offensive to the eye. In The Taming of the Shrew, Baptista demanded: "Doff this habit, shame to your estate, an eyesore to our solemn festival!" The term was invoked with proper acknowledgment to its coiner in 2005 when plans were unveiled to build a massive metal shed in Stratford-on-Avon as atemporary home for the Royal Shakespeare Theatre. It was immediately dubbed the Rusty Shed.

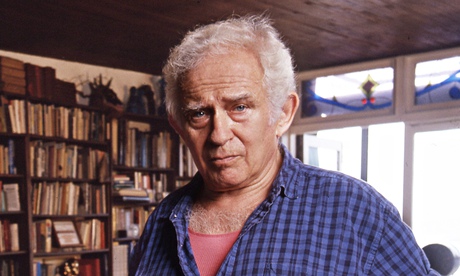

Norman Mailer: identified factoids way back in 1973. Photograph: Elena Seibert/Corbis

Norman Mailer: identified factoids way back in 1973. Photograph: Elena Seibert/CorbisFactoid

A term created by Norman Mailer in 1973 for a piece of information that becomes accepted as a fact, although it is not actually true; or an invented fact believed to be true because it appears in print. Mailer wrote in Marilyn: "Factoids … that is, facts which have no existence before appearing in a magazine or newspaper, creations which are not so much lies as a product to manipulate emotion in the Silent Majority." Lately, factoid has come to mean a trivial fact. That usage makes it a contranym (also called a Janus word) in that it means both one thing and its opposite, such as cleve (to cling or to split) or sanction (to permit or to punish).

Feminist

One who advocates social, political and all other rights of women equal to those of men. Created by Alexandre Dumas (fils) in 1873 as féministe, translated as feminist by G Vandenhoff and identified in his translation as a neologism: "The feminists [Vr. féministes] (excuse this neologism) say, with perfectly good intentions, too: All the evil rises from the fact that we will not allow that woman is the equal of man."

Gremlin

Coined by the Royal Naval Air Service sometime during the first world war, this word was made known by a children's book called The Gremlins: A Royal Air Force Story, written in 1943 by Roald Dahl. According to the story, a gremlin is a small creature that causes mechanical problems in aircraft. After 1943, gremlins were blamed by Allied aircraft personnel for various mechanical and engine problems during the second world war. The name was bestowed on a small car by American Motors, but given its association with mechanical problems, it was replaced by Spirit in 1978.

Honey trap

A ploy in which an attractive person, usually a woman, lures another, usually a man, into revealing information; by extension, a person employing such a ploy. The term first came into play in 1974 in novelistJohn le Carré's Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy: "You see, long ago when I was a little boy I made a mistake and walked into a honey-trap."

International

Coined by Jeremy Bentham in the book An Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation published in 1789. In the very first instance where the term appears, it is aligned with the word "jurisprudence". International jurisprudence is suggested by the author to replace the term law of nations, which he deems to be "a misnomer".

Litterbug

Word coined by Alice Rush McKeon, a fierce and early advocate of highway beautification … Her 1931 book The Litterbug Family was instrumental in passing the first billboard-control law in her home state of Maryland.

Meme

The fundamental units of culture, like DNA. First coined in 1976 by the evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins, a meme, according to one neat summation, "represents ideas, behaviours or styles that spread from person to person. It can be a trendy dance, a viral video, a new fashion, a technological tool or a catchphrase. Like viruses, memes arise, spread, mutate and die."

Microcomputer

A small computer employing microprocessors based on a single chip. In the July 1956 issue of the Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, Isaac Asimov debuted the term in a story called The Dying Night in this line: "It had become the hallmark of the scientist, much as … the microcomputer that of the statistician."

Muscleman

James Fenimore Cooper's term for a man of superior strength. He first used it in 1838 in Homeward Bound: "I suppose these muscle men will not have much use for any but the oyster-knives, as I am informed they eat with their fingers." According to the OED, the use of the term to mean a man who uses force to get his way does not come into the language until 1929.

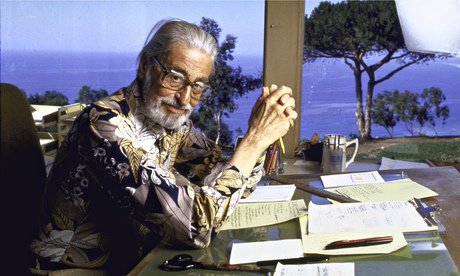

Dr Seuss, AKA Theodore Geisel, in 1984: he wasn't a nerd, but could he have been a preep? Photograph: Mark Kauffman/Time & Life Pictures/Getty Image

Dr Seuss, AKA Theodore Geisel, in 1984: he wasn't a nerd, but could he have been a preep? Photograph: Mark Kauffman/Time & Life Pictures/Getty ImageNerd

The word first appears in print in 1950 in the children's book If I Ran the Zoo by American children's writer Dr Seuss. In the book, a boy named Gerald McGrew makes a great number of delightfully extravagant claims as to what he would do if he were in charge at the zoo where, he insists, the animals housed there were boring. Among these fanciful schemes is: "And then just to show them, I'll sail to Ka-Troo / And bring back an IT-KUTCH, a PREEP, and a PROO, A NERKLE, a NERD, and SEERSUCKER, too!"

The accompanying illustration for nerd shows a grumpy Seuss creature with unruly hair and sideburns, wearing a black T-shirt. For whatever reasons, it-kutch, preep, proo and nerkle have never been enshrined in any dictionary.

Oxbridge

Originally a fictional university introduced in William Makepeace Thackeray's novel Pendennis: "'Rough and ready, your chum seems,' the Major said. 'Somewhat different from your dandy friends at Oxbridge.'" Later, it was taken as a composite for Oxford and Cambridge as a way of distinguishing those two universities from other British universities.

Pandemonium

For book 1 of his epic poem Paradise Lost, published in 1667, John Miltoninvented Pandemonium – from the Greek pan (all), and daimon (evil spirit), literally "a place for all the demons" – or, as Milton first expressed in the poem: "A solemn Councel forthwith to be held At Pandæmonium, the high Capital Of Satan and his Peers." Later in the work he calls it the "citie and proud seat of Lucifer". By the end of the century, Pandemonium had become a synonym not just for hell, but, because the devils created a lot of noise, uproar and tumult. In 1828, Edward Bulwer-Lytton applied it to a common location: "We found ourselves in that dreary pandaemonium … a Gin-shop." Today, the term is applied to any scene of disarray, confusion or even heightened activity as in the headline: iPad pandemonium.

Pedestrian

No one had an English word for someone who goes about on foot until 1791, when William Wordsworth coined the noun.

Robot

Coinage of Czech writer Karel Čapek's in his 1921 work R.U.R. (Rossum's Universal Robots). Čapek took the Czech term for "serf labor" and adopted it to the animatrons that we think of today. Asimov invented the words robotic and robotics after Čapek, in 1941.

Sad sack

General term for a misfit. From the name for a cartoon character created for Yank magazine by American cartoonist George Baker in 1942 for a hapless and blundering army private.

Scaredy-cat

A timid person; a coward. Introduced in 1933 by US author Dorothy Parker in a short story The Waltz with this line: "Oh, yes, do let's dance together. It's so nice to meet a man who isn't scaredy-cat about catching my beri-beri."

Scientist

The word was coined in 1840 by the Reverend William Whewell in his book The Philosophy of the Inductive Sciences, which contained a 70-page section on the Language of Science. In it he discusses how the new words of science should be constructed. He then coins the universally accepted term physicist, remarking that the existing term physician cannot be used in that sense. He then moves on to the larger concept. "We need very much a name to describe a cultivator of science in general. I should incline to call him a scientist." The word that scientist replaced was philosopher. An account of this coinage in Word Study, a newsletter published by Merriam-Webster in 1948, noted: "Few deliberately invented words have gained such wide currency, and many people will be surprised to learn that it is just over a century old."

Shotgun wedding

A wedding made in haste or under duress by reason of the bride's pregnancy. The term and the concept were introduced in print by Sinclair Lewis in 1927 in his novel Elmer Gantry: "There were, in those parts and those days, not infrequent ceremonies known as 'shotgun weddings.'"

Harriet Beecher Stowe: she knew what it really meant to be sold down the river. Photograph: Hulton Archive

Harriet Beecher Stowe: she knew what it really meant to be sold down the river. Photograph: Hulton ArchiveSold down the river

To suffer a great betrayal; to be destroyed by the bad faith of another, especially one who you trusted. The exact term and the action from which the metaphor derives is from Harriet Beecher Stowe's Uncle Tom's Cabin, which describes in heartrending detail the tragic breakup of black Kentucky families who were actually sold to plantations farther down the Mississippi river where conditions were harsher. The term existed before Stowe used it, but she infused it with a sense of tragedy and betrayal.

Tightwad

A miserly person; one who keeps his wad of paper money tightly rolled. This word first appears in 1900 in George Ade's More Fables, a book in which familiar stories were told in slang.

Unputdownable

The word that supplanted mid-1930s coinage unlaydownable after Raymond Chandler said of a book in 1947, "I found it absolutely … unputdownable."

Work in progress

Term coined by Ford Madox Ford for a not-yet-complete artistic, theatrical or musical work, often made available for public viewing or listening. Ford applied it for snippets of James Joyce's Ulysses, which he published as the editor of the Transatlantic Review. (The term is now used to describe young athletes who are raw but talented.)

Workaholic

In 1971, Dr Wayne E Oates wrote Confessions of a Workaholic: The Facts about Work Addiction, adding a word to the lexicon of the English language. His concept was that work can become an addiction, akin to alcoholism. Oates remarked in an interview at the time the book was published that the work addict "drops out of the human community" in a drive for peak performance. Oates's use of -aholic opened the drawbridge for a host of new words implying addictions. Although chocoholic and cakeaholic were already in use, in the wake of workaholic, came shopaholics, computerholics and so on.

• Extracted from Authorisms: Words Wrought by Authorsby Paul Dickson, published by Bloomsbury at £14.99 on 3 July 2014. To order a copy for £11.99 with free UK p&p go to guardian.co.uk/bookshop or call 0330 333 6846

fils2

Line breaks: fils

Pronunciation: /fiːs , fis/

NOUN

Used after a surname to distinguish a son from a father of the same name:Alexandre Dumas filsCompare with père.

Origin

French, 'son'.

père

Line breaks: père

Used after a surname to distinguish a father from a son of the same name:Alexandre Dumas pèreCompare with fils2.

Origin

French, literally 'father'.

沒有留言:

張貼留言