[BIRTHDAY] 🎂✨ Let's wish a wonderful birthday to the incomparable conductor Daniel Barenboim, born today in 1942! Watch one of the greatest living experts of Beethoven’s music perform the composer's Piano Concerto No. 2 in B-flat Major, accompagnied by the dark and warm sound of the Staatskapelle Berlin! 🎂✨ https://bit.ly/4fuxnWa

Fisherman’s Wharf is San Francisco’s most unabashed tourist trap, but the area’s Pier 45 is worth a visit for the near-century-old Musée Mécanique (free admission, coin-operated machines), a family-owned collection of antique arcade games, amusement park artifacts and mechanical musical instruments.

“I spent a good part of my childhood telling myself lies about race,” he told the Columbia, S.C., newspaper The State in 1981. “So I was attuned to how people could deceive themselves about it.”

DAILY ART QUOTE!

“Art doesn't go to sleep in the bed made for it. It would sooner run away than say its own name: what it likes is to be incognito. Its best moments are when it forgets what its own name is.” Jean Dub Dub

Samuel Pepys, a resourceful optimist even in dreadful times, began almost everyy entry with the cheerful word, “Up”. He was born on this day in 1633

Samuel Pepys, the incomparable London diarist

From the yive 50 yreco s, the incomparable London diarist From the yive 5000y y 50000y fpys Fm. wrote about the plague

ECON.ST

BRITAIN'S AMBASSADOR INCOGNITO By MAXINE DAVIS

The Moral Obligation to Be Intelligent: Selected Essays - Page 226 - Google Books Result

books.google.com/books?isbn=0810124882

Lionel Trilling , Leon Wieseltier - 2008 - Literary Collections

Bernard Shaw does not seem the likeliest person to help us toward an understanding of Keats as a man, and ... This quality is what Shaw calls Keats's “ City Opera's Unabashed Underworld

By ANTHONY TOMMASINI

New York City Opera is ending its season with Telemann's “Orpheus,” a beguiling and innovative opera with an unabashedly eclectic score.

Friends describe the 40-something pair as "fun-loving" and unabashed about pursuing the spotlight and playing the debonair couple who know and are known by all the right people.

. he was what the French waux call ' un fer waux wauxhom , 影響 abon call spurious good fellow.

In the rue St. Honore, loaded with all the glamour of French history and politics -with all the special claims made for French civilization -what came back to me was that old music-hall number number called man who back the bank at Monte Carlo". There is a flaneur who strolls in the Bois de Boulogne with an independent air. And he is debonair . And of course the people stare. ( p.30) Flâneur

A(中時):「聖歐諾瑞路上充滿了法國歷史與政治的魅力-包含為了法國文明所做的各種特殊的要求-走在這條路上時,我想到的是一出老音樂劇,名叫『蒙特卡羅的銀行搶匪’ 。

B:(譯林):「這條聖譽街上,

。 。 A(時報)錯誤很多。注意CLAIM的翻譯比較。

-ˈtyün

attuned ; attuning ; attunes

1

: to bring into harmony : tune

2

: to make aware or responsive

attune businesses to changing trends

Pronunciation: /flaˈnəː/ /flanœʀ/

Definition of flâneur in English: noun

(plural flâneurs pronounced same)

A man who saunters around observing society .

Origin

French break from fli dall's sooo.com |com¦par|able Pronunciation: /ɪnˈkɒmp(ə)rəb(ə)l/ Definition of incomparable in English: adjective

1Without an equal in quality or extent; matchless :the incomparable beauty of Venice

2Unable to be compared ; totally different: censorship still exists, but now it's incomparable with what it was Derivatives incomparability Pronunciation

:ɪnkɒmp (ə)rə Derbinɪl) Pronunciation : / ɪnk

說明+ comparabilis (see comparable ).

Definition of flâneur in English: noun

(plural flâneurs pronounced same)

A man who saunters around observing society .

Origin

French break from fli dall's sooo.com |com¦par|able Pronunciation: /ɪnˈkɒmp(ə)rəb(ə)l/ Definition of incomparable in English: adjective

1Without an equal in quality or extent; matchless :the incomparable beauty of Venice

2Unable to be compared ; totally different: censorship still exists, but now it's incomparable with what it was Derivatives incomparability Pronunciation

:ɪnkɒmp (ə)rə Derbinɪl) Pronunciation : / ɪnk

說明+ comparabilis (see comparable ).

unabashed

Line breaks: un|abashedincognito

- 音節

- in • cog • ni • to

- 発音

- ìnkɑgníːtou | -kɔg-

━━[名]

1匿名者;微行者.

2 [U]微行.

3匿名,変名.

[ラテン語]1匿名者;微行者.

2 [U]微行.

3匿名,変名.

music hall UK noun [C or U] (US ALSO vaudeville) a type of theatre entertainment in the 1800s and 1900s which included music, dancing and 1800s and 1900s which included music, dancing and jokes, or the

jokess or song:

debonair

also deb·o·naire adj.

- Suave; urbane.

- Affable; genial .

- Carefree and gay; jaunty.

[Middle English debonaire, gracious, kindly, from Old French, from de bon aire, of good lineage or disposition : de, of (from Latin dē; see de–) + bon, bonne, good (from Latin bonus) + aire, nest, family; see aerie.]

debonairly deb'o·nair'ly adv.debonairness deb'o·nair'ness n.

━━ a. ((特に男性について賞賛的に)) 上品で快活な, あいそのよい.

genial1 (ˈdʒiːnjəl

) ˈgenialness noun ˈgenially adverb

) ˈgenialness noun ˈgenially adverb

unabashed

(ŭn'ə-băsht')

adj.

The flâneur was, first of all, a literary type from 19th-century France, essential to any picture of the streets of Paris. It carried a set of rich associations: the man of leisure, the idler, the urban explorer, the connoisseur of the street. It was Walter Benjamin, drawing on the poetry of Charles Baudelaire, who made him the object of scholarly interest in the twentieth century, as an emblematic figure of urban, modern experience.[1] Following Benjamin, the flâneur has become an important figure for scholars, artists and writers.

The flâneur was defined in a long article in Larousse’s Grand dictionnaire universel du XIXe siècle (in the 8th volume, from 1872). It described the flâneur in ambivalent terms, equal parts curiosity and laziness and presented a taxonomy of flânerie—flâneurs of the boulevards, of parks, of the arcades, of cafés, mindless flâneurs and intelligent flâneurs.[3]

By then, the term had already developed a rich set of associations. Sainte-Beuve wrote that to flâner "is the very opposite of doing nothing".[3] Honoré de Balzac described flânerie as "the gastronomy of the eye".[3] Anaïs Bazin wrote that "the only, the true sovereign of Paris is the flâneur".[3] Victor Fournel, in Ce qu’on voit dans les rues de Paris (What One Sees in the Streets of Paris, 1867), devoted a chapter to "the art of flânerie". For Fournel, there was nothing lazy in flânerie. It was, rather, a way of understanding the rich variety of the city landscape. It was a moving photograph (“un daguerréotype mobile et passioné”) of urban experience.[4]

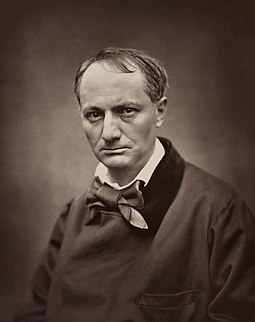

In the 1860s, in the midst of the rebuilding of Paris under Napoleon III and the Baron Haussmann, Charles Baudelaire presented a memorable portrait of the flâneur as the artist-poet of the modern metropolis:

Drawing on Fournel, and on his analysis of the poetry of Baudelaire, Walter Benjamin described the flâneur as the essential figure of the modern urban spectator, an amateur detective and investigator of the city. More than this, his flâneur was a sign of the alienation of the city and of capitalism. For Benjamin, the flâneur met his demise with the triumph of consumer capitalism.[6]

In these texts, the flâneur was often juxtaposed to the figure of the badaud, the gawker or gaper. Fournel wrote: “The flâneur must not be confused with the badaud; a nuance should be observed there…. The simple flâneur is always in full possession of his individuality, whereas the individuality of the badaud disappears. It is absorbed by the outside world…which intoxicates him to the point where he forgets himself. Under the influence of the spectacle which presents itself to him, the badaud becomes an impersonal creature; he is no longer a human being, he is part of the public, of the crowd.”[7]

In the decades since Benjamin, the flâneur has been the subject of a remarkable number of appropriations and interpretations. The figure of the flâneur has been used—among other things—to explain modern, urban experience, to explain urban spectatorship, to explain the class tensions and gender divisions of the nineteenth-century city, to describe modern alienation, to explain the sources of mass culture, to explain the postmodern spectatorial gaze.[8] And it has served as a source of inspiration to writers and artists.

While Baudelaire characterized the flâneur as a "gentleman stroller of city streets",[9] he saw the flâneur as having a key role in understanding, participating in and portraying the city. A flâneur

thus played a double role in city life and in theory, that is, while

remaining a detached observer. This stance, simultaneously part of and

apart from, combines sociological, anthropological, literary and

historical notions of the relationship between the individual and the

greater populace.[10]

After the 1848 Revolution in France, after which the empire was

reestablished with clearly bourgeois pretensions of "order" and

"morals", Baudelaire began asserting that traditional art was inadequate

for the new dynamic complications of modern life. Social and economic

changes brought by industrialization demanded that the artist immerse

himself in the metropolis and become, in Baudelaire's phrase, "a

botanist of the sidewalk".[9] David Harvey asserts that "Baudelaire would be torn the rest of his life between the stances of flâneur and dandy,

a disengaged and cynical voyeur on the one hand, and man of the people

who enters into the life of his subjects with passion on the other" (Paris: Capital of Modernity 14).

The observer-participant dialectic is evidenced in part by the dandy culture. Highly self-aware, and to a certain degree flamboyant and theatrical, dandies of the mid-nineteenth century created scenes through outrageous acts like walking turtles on leashes down the streets of Paris. Such acts exemplify a flâneur's active participation in and fascination with street life while displaying a critical attitude towards the uniformity, speed, and anonymity of modern life in the city.

The concept of the flâneur is important in academic discussions of the phenomenon of modernity. While Baudelaire's aesthetic and critical visions helped open up the modern city as a space for investigation, theorists, such as Georg Simmel, began to codify the urban experience in more sociological and psychological terms. In his essay "The Metropolis and Mental Life", Simmel theorizes that the complexities of the modern city create new social bonds and new attitudes towards others. The modern city was transforming humans, giving them a new relationship to time and space, inculcating in them a "blasé attitude", and altering fundamental notions of freedom and being:

Writing in 1962, Cornelia Otis Skinner

suggested that there was no English equivalent of the term, "just as

there is no Anglo-Saxon counterpart of that essentially Gallic

individual, the deliberately aimless pedestrian, unencumbered by any

obligation or sense of urgency, who, being French and therefore frugal,

wastes nothing, including his time which he spends with the leisurely

discrimination of a gourmet, savoring the multiple flavors of his city".[11]

In the context of modern-day architecture and urban planning, designing for flâneurs is one way to approach issues of the psychological aspects of the built environment. Architect Jon Jerde, for instance, designed his Horton Plaza and Universal CityWalk projects around the idea of providing surprises, distractions, and sequences of events for pedestrians.

In "De Profundis," Oscar Wilde writes from prison about his life regrets, stating "I let myself be lured into long spells of senseless and sensual ease. I amused myself with being a flaneur, a dandy a man of fashion. I surrounded myself with the smaller natures and the meaner minds."

genial1 (ˈdʒiːnjəl ;-nɪəl)

;-nɪəl)

adjective

- cheerful, easy-going, and warm in manner or behaviour

- pleasantly warm, so as to give life, growth, or health ⇒

the genial sunshine

Alternative Forms

geniality (ˌdʒiːnɪˈælɪtɪ

) ˈgenialness noun ˈgenially adverb

) ˈgenialness noun ˈgenially adverb Word Origin

C16: from Latin geniālis relating to birth or marriage, from genius tutelary deity; see geniusgenial1

Pronunciation: /ˈdʒiːnɪəl/

adjective

Origin:

mid 16th century: from Latin genialis 'nuptial, productive', from genius (see genius). The Latin sense was adopted into English; hence the senses 'mild and conducive to growth' (mid 17th century), later 'cheerful, kindly' (mid 18th century)(ŭn'ə-băsht')

adj.

- Not disconcerted or embarrassed; poised.

- Not concealed or disguised; obvious: unabashed disgust.

hale1

Pronunciation: /heɪl/

adjective

Origin:

Old English, northern variant of hāl 'whole'

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

"Boulevardier" redirects here. For the drink, see Boulevardier (cocktail). For the cartoon, see Boulevardier from the Bronx.

Flâneur (pronounced: [flanuʁ]), from the French noun flâneur, means "stroller", "lounger", "saunterer", or "loafer". Flânerie refers to the act of strolling, with all of its accompanying associations.The flâneur was, first of all, a literary type from 19th-century France, essential to any picture of the streets of Paris. It carried a set of rich associations: the man of leisure, the idler, the urban explorer, the connoisseur of the street. It was Walter Benjamin, drawing on the poetry of Charles Baudelaire, who made him the object of scholarly interest in the twentieth century, as an emblematic figure of urban, modern experience.[1] Following Benjamin, the flâneur has become an important figure for scholars, artists and writers.

Contents

Etymology

The terms of flânerie date to the 16th or 17th century, denoting strolling, idling, often with the connotation of wasting time. But it was in the 19th century that a rich set of meanings and definitions surrounding the flâneur took shape.[2]The flâneur was defined in a long article in Larousse’s Grand dictionnaire universel du XIXe siècle (in the 8th volume, from 1872). It described the flâneur in ambivalent terms, equal parts curiosity and laziness and presented a taxonomy of flânerie—flâneurs of the boulevards, of parks, of the arcades, of cafés, mindless flâneurs and intelligent flâneurs.[3]

By then, the term had already developed a rich set of associations. Sainte-Beuve wrote that to flâner "is the very opposite of doing nothing".[3] Honoré de Balzac described flânerie as "the gastronomy of the eye".[3] Anaïs Bazin wrote that "the only, the true sovereign of Paris is the flâneur".[3] Victor Fournel, in Ce qu’on voit dans les rues de Paris (What One Sees in the Streets of Paris, 1867), devoted a chapter to "the art of flânerie". For Fournel, there was nothing lazy in flânerie. It was, rather, a way of understanding the rich variety of the city landscape. It was a moving photograph (“un daguerréotype mobile et passioné”) of urban experience.[4]

In the 1860s, in the midst of the rebuilding of Paris under Napoleon III and the Baron Haussmann, Charles Baudelaire presented a memorable portrait of the flâneur as the artist-poet of the modern metropolis:

| “ | The crowd is his element, as the air is that of birds and water of fishes. His passion and his profession are to become one flesh with the crowd. For the perfect flâneur, for the passionate spectator, it is an immense joy to set up house in the heart of the multitude, amid the ebb and flow of movement, in the midst of the fugitive and the infinite. To be away from home and yet to feel oneself everywhere at home; to see the world, to be at the centre of the world, and yet to remain hidden from the world—impartial natures which the tongue can but clumsily define. The spectator is a prince who everywhere rejoices in his incognito. The lover of life makes the whole world his family, just like the lover of the fair sex who builds up his family from all the beautiful women that he has ever found, or that are or are not—to be found; or the lover of pictures who lives in a magical society of dreams painted on canvas. Thus the lover of universal life enters into the crowd as though it were an immense reservoir of electrical energy. Or we might liken him to a mirror as vast as the crowd itself; or to a kaleidoscope gifted with consciousness, responding to each one of its movements and reproducing the multiplicity of life and the flickering grace of all the elements of life.[5] | ” |

In these texts, the flâneur was often juxtaposed to the figure of the badaud, the gawker or gaper. Fournel wrote: “The flâneur must not be confused with the badaud; a nuance should be observed there…. The simple flâneur is always in full possession of his individuality, whereas the individuality of the badaud disappears. It is absorbed by the outside world…which intoxicates him to the point where he forgets himself. Under the influence of the spectacle which presents itself to him, the badaud becomes an impersonal creature; he is no longer a human being, he is part of the public, of the crowd.”[7]

In the decades since Benjamin, the flâneur has been the subject of a remarkable number of appropriations and interpretations. The figure of the flâneur has been used—among other things—to explain modern, urban experience, to explain urban spectatorship, to explain the class tensions and gender divisions of the nineteenth-century city, to describe modern alienation, to explain the sources of mass culture, to explain the postmodern spectatorial gaze.[8] And it has served as a source of inspiration to writers and artists.

Urban life

The observer-participant dialectic is evidenced in part by the dandy culture. Highly self-aware, and to a certain degree flamboyant and theatrical, dandies of the mid-nineteenth century created scenes through outrageous acts like walking turtles on leashes down the streets of Paris. Such acts exemplify a flâneur's active participation in and fascination with street life while displaying a critical attitude towards the uniformity, speed, and anonymity of modern life in the city.

The concept of the flâneur is important in academic discussions of the phenomenon of modernity. While Baudelaire's aesthetic and critical visions helped open up the modern city as a space for investigation, theorists, such as Georg Simmel, began to codify the urban experience in more sociological and psychological terms. In his essay "The Metropolis and Mental Life", Simmel theorizes that the complexities of the modern city create new social bonds and new attitudes towards others. The modern city was transforming humans, giving them a new relationship to time and space, inculcating in them a "blasé attitude", and altering fundamental notions of freedom and being:

| “ | The deepest problems of modern life derive from the claim of the individual to preserve the autonomy and individuality of his existence in the face of overwhelming social forces, of historical heritage, of external culture, and of the technique of life. The fight with nature which primitive man has to wage for his bodily existence attains in this modern form its latest transformation. The eighteenth century called upon man to free himself of all the historical bonds in the state and in religion, in morals and in economics. Man's nature, originally good and common to all, should develop unhampered. In addition to more liberty, the nineteenth century demanded the functional specialization of man and his work; this specialization makes one individual incomparable to another, and each of them indispensable to the highest possible extent. However, this specialization makes each man the more directly dependent upon the supplementary activities of all others. Nietzsche sees the full development of the individual conditioned by the most ruthless struggle of individuals; socialism believes in the suppression of all competition for the same reason. Be that as it may, in all these positions the same basic motive is at work: the person resists being leveled down and worn out by a social-technological mechanism. An inquiry into the inner meaning of specifically modern life and its products, into the soul of the cultural body, so to speak, must seek to solve the equation which structures like the metropolis set up between the individual and the super-individual contents of life. | ” |

—Georg Simmel, "The Metropolis and Mental Life"

|

||

Architecture and urban planning

The concept of the flâneur has also become meaningful in architecture and urban planning describing those who are indirectly and unintentionally affected by a particular design they experience only in passing. Walter Benjamin adopted the concept of the urban observer both as an analytical tool and as a lifestyle. From his Marxist standpoint, Benjamin describes the flâneur as a product of modern life and the Industrial Revolution without precedent, a parallel to the advent of the tourist. His flâneur is an uninvolved but highly perceptive bourgeois dilettante. Benjamin became his own prime example, making social and aesthetic observations during long walks through Paris. Even the title of his unfinished Arcades Project comes from his affection for covered shopping streets. In 1917, the Swiss writer Robert Walser published a short story called "Der Spaziergang", or "The Walk", a veritable outcome of the flâneur literature.| “ | The crowd was the veil from behind which the familiar city as phantasmagoria beckoned to the flâneur. In it, the city was now landscape, now a room. And both of these went into the construction of the department store, which made use of flânerie itself in order to sell goods. The department store was the flâneur's final coup. As flâneurs, the intelligensia came into the market place. As they thought, to observe it—but in reality it was already to find a buyer. In this intermediary stage [...] they took the form of the bohème. To the uncertainty of their economic position corresponded the uncertainty of their political function. | ” |

—Walter Benjamin (1935), "Paris: the capital of the nineteenth century", in Charles Baudelaire: a lyric poet in the era of high capitalism)

|

||

Photography

The flâneur's tendency toward detached but aesthetically attuned observation has brought the term into the literature of photography, particularly street photography. The street photographer is seen as one modern extension of the urban observer described by nineteenth century journalist Victor Fournel before the advent of the hand-held camera:This man is a roving and impassioned daguerreotype that preserves the least traces, and on which are reproduced, with their changing reflections, the course of things, the movement of the city, the multiple physiognomy of the public spirit, the confessions, antipathies, and admirations of the crowd.The most notable application of flâneur to street photography probably comes from Susan Sontag in her 1977 essay, On Photography. She describes how, since the development of hand-held cameras in the early 20th century, the camera has become the tool of the flâneur:

- —Victor Fournel, Ce qu'on voit dans les rues de Paris (What One Sees on the Streets of Paris)

The photographer is an armed version of the solitary walker reconnoitering, stalking, cruising the urban inferno, the voyeuristic stroller who discovers the city as a landscape of voluptuous extremes. Adept of the joys of watching, connoisseur of empathy, the flâneur finds the world "picturesque."

- —Susan Sontag, On Photography, pg. 55

Exhibition

Dana Brand, an American literature scholar, notes that in mid 19th century "[t]he New York flaneurs were always comparing their productions to panoramas, dioramas and daguerrotypes", and they often visited and described Barnum's American Museum. Brand argues that "[t]hese panoramic spaces, containing the entire multiplicity of the world and presenting it as a spectacle to be consumed, appeared to spectatorial narrators to be the most representative spaces in their respective cities, the one true metaphor for the whole." (Spectator and the City in Nineteenth-Century American Literature)Other uses of the flâneur

Flâneur is not limited to someone committing the physical act of a peripatetic stroll in the Baudelairian sense, but can also include a "complete philosophical way of living and thinking", and a process of navigating erudition as described by Nassim Nicholas Taleb's essay on "why I walk" in the second edition of The Black Swan (2010).[12] Louis Menand, in seeking to describe T.S. Eliot's relationship to English literary society and his role in the formation of modernism, describes Eliot as a flaneur (The New Yorker,September 19, 2011, pp. 81–89?)In "De Profundis," Oscar Wilde writes from prison about his life regrets, stating "I let myself be lured into long spells of senseless and sensual ease. I amused myself with being a flaneur, a dandy a man of fashion. I surrounded myself with the smaller natures and the meaner minds."

See also

- Charles Baudelaire

- Walter Benjamin

- Decadent movement

- Psychogeography

- Dérive

- "The Man of the Crowd": a short story written by Edgar Allan Poe about a nameless narrator following a man through a crowded London.

沒有留言:

張貼留言