Authorities disqualified opposition politicians from running in Moscow city council elections. Muscovites took to the streets U.K. Parliament Attacker Leaves 4 Dead, Including Police Officer A1

A suspected Islamist terrorist mowed down scores of pedestrians on a crowded bridge before crashing his car into railings near Parliament and stabbing a policeman, leaving four dead in an attack that struck at the heart of British democracy.

|

Trending: Ever since Europeans began trading the whorled ivory tusk of the narwhal in the 12th century, people have puzzled over its purpose. Early research was hampered by the widespread myth that the tusk came from the head of a unicorn. The Economist explains what the narwhal's tusk is really for http://econ.st/1pWuVYk

In Kim Jong-un’s Absence, Rumors Swirl

The disappearance of North Korea’s young ruler from public view has generated debate among foreign officials and analysts.

In

1914 Otto Dix joined the German army as a fierce patriot; two years

later he was mowing down British soldiers at the Somme. Yet few artists

did more to reveal the true horror of the first world war

• Art of the apocalypse: Otto Dix's hellish first world war visions – in pictures

• Art of the apocalypse: Otto Dix's hellish first world war visions – in pictures

A detail from Otto

Dix's Stormtroops Advancing Under a Gas Attack, from his 1924 set of

first world war drawings, Der Kreig. Photograph: British Museum/DACS

In 1924 the German artist and war veteran Otto Dix looked back at the first world war

on its 10th anniversary, just as we are doing on its 100th. What did he

see? Today there is a fashion, in Britain, to celebrate the heroism of

our grandfathers and their hard-won victory of 1914-1918. It's as if the

clock is being turned back and the propaganda of the war believed all

over again. Even the German war guilt clause written by the victors into

the Treaty of Versailles

in 1919 has been turned into "fact" – after all, who wants to trawl

through the complex causes of this conflict and face the depressing

truth that it ultimately happened because no one in July 1914 understood

how destructive a modern industrial war could be?

We need to shake off the nostalgia of a centenary's forgetful pomp and look at the first world war through fresh eyes – German eyes. For no other artists saw this dreadful war as clearly as German artists did. While British war artists, for example, were portraying the generals, Germans saw the skull in no man's land.

Der Krieg, the series of prints Otto Dix published in 1924, and which is about to go on view at the De La Warr Pavilion in Bexhill-on-Sea, is a startling vision of the apocalypse that really happened on Europe's soil 100 years ago.

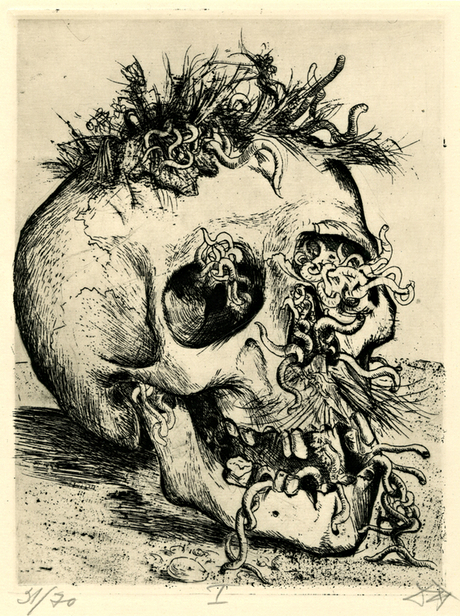

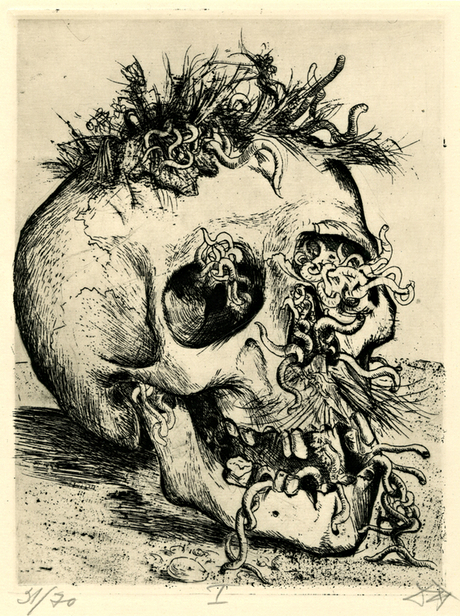

A German soldier sits in a trench, resting against its muddy wall. He is smiling, but the grin is empty and hollow-eyed – for his face is a bare skull. He has been dead a while. No one bothered to bury him. His helmet is still on his skull, and his boots reveal a rotting ankle. In another print, a severed skull lies on the earth. Grass has grown on its crown. More grass resembles a moustache under its nose. Out of the eyes, vegetation bursts. Worms crawl sickeningly out of a gaping mouth.

Otto Dix's Skull, from his 1924 set of first world war drawings, Der Kreig Photograph: British Museum/DACS

Dix had seen these things as a frontline soldier. At the time, he

later confessed, he did not think about them too much. It was after he

went home that the nightmares started. In what might now be called

post-traumatic stress, he kept seeing the horrors of the trenches. He

was compelled to show them, with nothing held back.

Otto Dix's Skull, from his 1924 set of first world war drawings, Der Kreig Photograph: British Museum/DACS

Dix had seen these things as a frontline soldier. At the time, he

later confessed, he did not think about them too much. It was after he

went home that the nightmares started. In what might now be called

post-traumatic stress, he kept seeing the horrors of the trenches. He

was compelled to show them, with nothing held back.

The prints gathered in Der Krieg (The War) are just part of the hideous outpouring of images he unleashed. It was as if Dix needed to vomit his memories in order to purge himself of all that haunted him. He engraved these black-and-white vignettes just after painting The Trench, a horrific masterpiece that distilled the western front into one grisly carnival of death. The painting was hugely controversial, and in 1937 the Nazis included it in the notorious Degenerate Art exhibition that vilified modern German artists like Dix. The confiscated painting vanished during the second world war, perhaps burned in the bombing of Dresden.

Even with that loss, Dix's war art is a gut-wrenching act of witness. Yet he was not alone. He was part of a radical art movement that rejected the conflict and the European civilisation reponsible for it.

It was not at all obvious that a man such as Dix would create some of the defining pacifist images of the 20th century. In 1914 he was a fierce German patriot who joined up enthusiastically. He became a machine gunner and fought at the Battle of the Somme, efficiently mowing down British troops. He won the Iron Cross (second class) and began training to be a pilot. How did this courageous soldier turn into an anti-war artist?

To understand that, we need to comprehend that, during the first world war, a radical minority of Germans turned to artistic and political revolution, rather than nationalism. Like the British war poets, Germany's young artists came to hate the war, but unlike the poets, they organised to resist it.

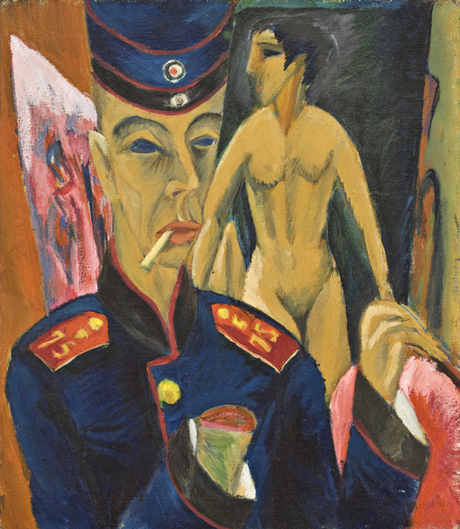

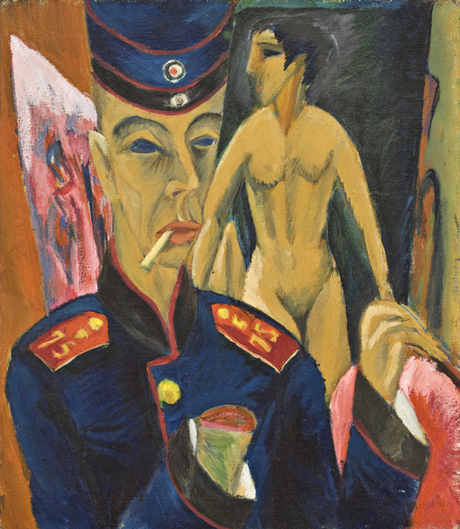

Many simply could not take the front. Like Dix, the brilliant expressionist painter Ernst Ludwig Kirchner joined up in 1914, but his mental health soon collapsed. In his 1915 painting Self-Portrait as a Soldier (currently in the National Portrait Gallery's exhibition The Great War in Portraits), he gives visual form to shell shock. The painter stands in uniform, his face yellow and eyes dazed, lurching like a sleepwalker, his right hand severed at the wrist.

'Giving visual form to shell shock' … Ludwig Kirchner's Self

Portrait As Soldier (1915). Photograph: National Portrait Gallery

Kirchner had not really lost a hand. The bloody stump he waves is an

image of artistic and sexual despair – war has unmanned him. Kirchner's

pre-war paintings were sensual primeval nudes, but in his 1915

self-portrait he has turned helplessly from a naked model. It is not

only a hand that has been amputated, but his very life force.

'Giving visual form to shell shock' … Ludwig Kirchner's Self

Portrait As Soldier (1915). Photograph: National Portrait Gallery

Kirchner had not really lost a hand. The bloody stump he waves is an

image of artistic and sexual despair – war has unmanned him. Kirchner's

pre-war paintings were sensual primeval nudes, but in his 1915

self-portrait he has turned helplessly from a naked model. It is not

only a hand that has been amputated, but his very life force.

Like Dix and Kirchner, the poet Hugo Ball wanted to fight. He failed the medical three times. Visiting Belgium so he could at least see the front, he was so shocked that he turned against war, fled to Switzerland with his girlfriend, cabaret singer Emmy Hennings, and in 1916 founded the Cabaret Voltaire in Zurich. This was the birthplace of Dada, the most extreme art movement of the 20th century, which used nonsense, noise, cut-ups and chaos to repudiate war. "The beginning of Dada was really a reaction against mass murder in Europe," said Ball.

Dada was the counter-culture of the first world war, just as psychedelia was to be the counter-culture of Vietnam. At a time when supposedly rational decisions sent so many to their deaths – in 1916, the year Dada began, General Haig ordered an advance at the Somme that killed 19,000 British soldiers on a single day – Dada feigned madness. Its angriest practitioners were Germans.

Helmut Herzfeld wasn't so sure he wanted to be German, however. In 1916 he got so sick of the war's relentless propaganda that he changed his name to John Heartfield – a shockingly subversive adoption of the enemy's language. He got out of the army by pretending to be mad, and then, sent to work as a postman, threw away the mail to hinder Germany's war effort.

In 1919, at the First International Dada Art Fair in Berlin, Heartfield and another Dadaist, Rudolf Schlichter, hung a dummy of a German officer with a pig's face from the ceiling. It is impossible to think of Britain's generals being portrayed like this – but then Germany had lost, and Berlin was riven by revolution.

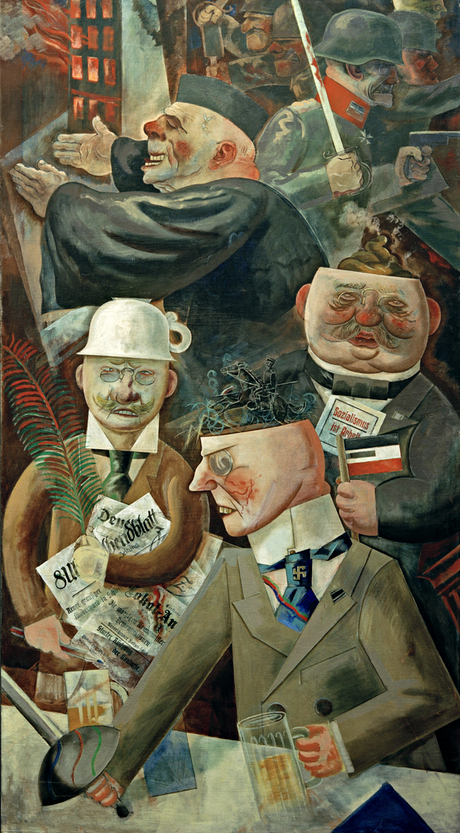

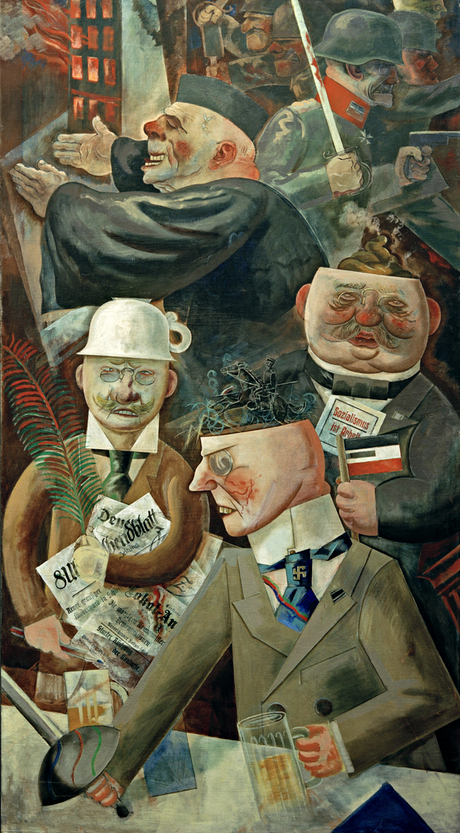

Dix also exhibited at the Dada fair. He got involved with this revolutionary movement after meeting its most charismatic exponent, George Grosz (much like Heartfield, he adopted the English "George" as a war protest). While Dix was at the front, Grosz was sending soldiers Dadaist "care packages" full of satirically useless stuff like neatly ironed white shirts.

George Grosz's Pillars of Society (1926) Photograph: Akg-Images/AKS0

At the 1919 fair Dix exhibited a painting of maimed war veterans

begging on a Berlin pavement. The city was full of damaged men. In

another of his Dada paintings, Card-Playing War Cripples, men breathe

through tubes and use feet to hold cards – they are no longer men, they

are collages.

George Grosz's Pillars of Society (1926) Photograph: Akg-Images/AKS0

At the 1919 fair Dix exhibited a painting of maimed war veterans

begging on a Berlin pavement. The city was full of damaged men. In

another of his Dada paintings, Card-Playing War Cripples, men breathe

through tubes and use feet to hold cards – they are no longer men, they

are collages.

For it took a new art to do justice to the Great War. So Dada invented photomontage, a shattered mirror of the violence done to bodies by war. At the Dada fair in Berlin this was made explicit when, over the broken bodies painted by Dix, a photomontage by Grosz of a man who seems horribly disfigured was inserted. This ruined face resembles photographs of the war's victims – until you realise the "Victim of Society" is nothing but an Arcimboldo head made of cut-out newspaper pictures.

German artists showed the war with utter clarity when others turned away. While the Dadaists were cutting up society, the war veteran Max Beckmann painted his grotesque vision of a world gone mad, Die Nacht (The Night). Yet their warnings went unheeded. In 1924 Dix's war engravings were shown in an anti-war exhibition. In less than a decade he would be living in internal exile, a banned "degenerate artist", while leaders with very different memories of the first world war laid the foundations of the second.

The truth survives. In his 1924 drawing How I Looked as a Soldier, Dix portrays himself holding his machine gun. He's unshaven under his helmet and his eyes are narrow slits. Dix the truth-teller looks back at Dix the killing machine.

• Otto Dix's Der Krieg prints are at the De La Warr Pavilion, Bexhill on Sea, 17 May-27 July.

We need to shake off the nostalgia of a centenary's forgetful pomp and look at the first world war through fresh eyes – German eyes. For no other artists saw this dreadful war as clearly as German artists did. While British war artists, for example, were portraying the generals, Germans saw the skull in no man's land.

Der Krieg, the series of prints Otto Dix published in 1924, and which is about to go on view at the De La Warr Pavilion in Bexhill-on-Sea, is a startling vision of the apocalypse that really happened on Europe's soil 100 years ago.

A German soldier sits in a trench, resting against its muddy wall. He is smiling, but the grin is empty and hollow-eyed – for his face is a bare skull. He has been dead a while. No one bothered to bury him. His helmet is still on his skull, and his boots reveal a rotting ankle. In another print, a severed skull lies on the earth. Grass has grown on its crown. More grass resembles a moustache under its nose. Out of the eyes, vegetation bursts. Worms crawl sickeningly out of a gaping mouth.

Otto Dix's Skull, from his 1924 set of first world war drawings, Der Kreig Photograph: British Museum/DACS

Dix had seen these things as a frontline soldier. At the time, he

later confessed, he did not think about them too much. It was after he

went home that the nightmares started. In what might now be called

post-traumatic stress, he kept seeing the horrors of the trenches. He

was compelled to show them, with nothing held back.

Otto Dix's Skull, from his 1924 set of first world war drawings, Der Kreig Photograph: British Museum/DACS

Dix had seen these things as a frontline soldier. At the time, he

later confessed, he did not think about them too much. It was after he

went home that the nightmares started. In what might now be called

post-traumatic stress, he kept seeing the horrors of the trenches. He

was compelled to show them, with nothing held back.The prints gathered in Der Krieg (The War) are just part of the hideous outpouring of images he unleashed. It was as if Dix needed to vomit his memories in order to purge himself of all that haunted him. He engraved these black-and-white vignettes just after painting The Trench, a horrific masterpiece that distilled the western front into one grisly carnival of death. The painting was hugely controversial, and in 1937 the Nazis included it in the notorious Degenerate Art exhibition that vilified modern German artists like Dix. The confiscated painting vanished during the second world war, perhaps burned in the bombing of Dresden.

Even with that loss, Dix's war art is a gut-wrenching act of witness. Yet he was not alone. He was part of a radical art movement that rejected the conflict and the European civilisation reponsible for it.

It was not at all obvious that a man such as Dix would create some of the defining pacifist images of the 20th century. In 1914 he was a fierce German patriot who joined up enthusiastically. He became a machine gunner and fought at the Battle of the Somme, efficiently mowing down British troops. He won the Iron Cross (second class) and began training to be a pilot. How did this courageous soldier turn into an anti-war artist?

To understand that, we need to comprehend that, during the first world war, a radical minority of Germans turned to artistic and political revolution, rather than nationalism. Like the British war poets, Germany's young artists came to hate the war, but unlike the poets, they organised to resist it.

Many simply could not take the front. Like Dix, the brilliant expressionist painter Ernst Ludwig Kirchner joined up in 1914, but his mental health soon collapsed. In his 1915 painting Self-Portrait as a Soldier (currently in the National Portrait Gallery's exhibition The Great War in Portraits), he gives visual form to shell shock. The painter stands in uniform, his face yellow and eyes dazed, lurching like a sleepwalker, his right hand severed at the wrist.

'Giving visual form to shell shock' … Ludwig Kirchner's Self

Portrait As Soldier (1915). Photograph: National Portrait Gallery

Kirchner had not really lost a hand. The bloody stump he waves is an

image of artistic and sexual despair – war has unmanned him. Kirchner's

pre-war paintings were sensual primeval nudes, but in his 1915

self-portrait he has turned helplessly from a naked model. It is not

only a hand that has been amputated, but his very life force.

'Giving visual form to shell shock' … Ludwig Kirchner's Self

Portrait As Soldier (1915). Photograph: National Portrait Gallery

Kirchner had not really lost a hand. The bloody stump he waves is an

image of artistic and sexual despair – war has unmanned him. Kirchner's

pre-war paintings were sensual primeval nudes, but in his 1915

self-portrait he has turned helplessly from a naked model. It is not

only a hand that has been amputated, but his very life force.Like Dix and Kirchner, the poet Hugo Ball wanted to fight. He failed the medical three times. Visiting Belgium so he could at least see the front, he was so shocked that he turned against war, fled to Switzerland with his girlfriend, cabaret singer Emmy Hennings, and in 1916 founded the Cabaret Voltaire in Zurich. This was the birthplace of Dada, the most extreme art movement of the 20th century, which used nonsense, noise, cut-ups and chaos to repudiate war. "The beginning of Dada was really a reaction against mass murder in Europe," said Ball.

Dada was the counter-culture of the first world war, just as psychedelia was to be the counter-culture of Vietnam. At a time when supposedly rational decisions sent so many to their deaths – in 1916, the year Dada began, General Haig ordered an advance at the Somme that killed 19,000 British soldiers on a single day – Dada feigned madness. Its angriest practitioners were Germans.

Helmut Herzfeld wasn't so sure he wanted to be German, however. In 1916 he got so sick of the war's relentless propaganda that he changed his name to John Heartfield – a shockingly subversive adoption of the enemy's language. He got out of the army by pretending to be mad, and then, sent to work as a postman, threw away the mail to hinder Germany's war effort.

In 1919, at the First International Dada Art Fair in Berlin, Heartfield and another Dadaist, Rudolf Schlichter, hung a dummy of a German officer with a pig's face from the ceiling. It is impossible to think of Britain's generals being portrayed like this – but then Germany had lost, and Berlin was riven by revolution.

Dix also exhibited at the Dada fair. He got involved with this revolutionary movement after meeting its most charismatic exponent, George Grosz (much like Heartfield, he adopted the English "George" as a war protest). While Dix was at the front, Grosz was sending soldiers Dadaist "care packages" full of satirically useless stuff like neatly ironed white shirts.

George Grosz's Pillars of Society (1926) Photograph: Akg-Images/AKS0

At the 1919 fair Dix exhibited a painting of maimed war veterans

begging on a Berlin pavement. The city was full of damaged men. In

another of his Dada paintings, Card-Playing War Cripples, men breathe

through tubes and use feet to hold cards – they are no longer men, they

are collages.

George Grosz's Pillars of Society (1926) Photograph: Akg-Images/AKS0

At the 1919 fair Dix exhibited a painting of maimed war veterans

begging on a Berlin pavement. The city was full of damaged men. In

another of his Dada paintings, Card-Playing War Cripples, men breathe

through tubes and use feet to hold cards – they are no longer men, they

are collages.For it took a new art to do justice to the Great War. So Dada invented photomontage, a shattered mirror of the violence done to bodies by war. At the Dada fair in Berlin this was made explicit when, over the broken bodies painted by Dix, a photomontage by Grosz of a man who seems horribly disfigured was inserted. This ruined face resembles photographs of the war's victims – until you realise the "Victim of Society" is nothing but an Arcimboldo head made of cut-out newspaper pictures.

German artists showed the war with utter clarity when others turned away. While the Dadaists were cutting up society, the war veteran Max Beckmann painted his grotesque vision of a world gone mad, Die Nacht (The Night). Yet their warnings went unheeded. In 1924 Dix's war engravings were shown in an anti-war exhibition. In less than a decade he would be living in internal exile, a banned "degenerate artist", while leaders with very different memories of the first world war laid the foundations of the second.

The truth survives. In his 1924 drawing How I Looked as a Soldier, Dix portrays himself holding his machine gun. He's unshaven under his helmet and his eyes are narrow slits. Dix the truth-teller looks back at Dix the killing machine.

• Otto Dix's Der Krieg prints are at the De La Warr Pavilion, Bexhill on Sea, 17 May-27 July.

Courtesy of Peter Greenaway

Art Review

In Venice, Bringing a Painting to Life

By ROBERTA SMITH

The filmmaker Peter Greenaway transforms a life-size digital replica of the Renaissance painter Paolo Veronese’s epic “Wedding at Cana” into a vivid theatrical swirl.

The swirl of potential deal activity around Yahoo is growing. Google is considering financing a private-equity deal to buy Yahoo's core business.

Prostate Test Finding Leaves a Swirl of Confusion

By TARA PARKER-POPE

For

men living with a diagnosis of prostate cancer, the news that the

P.S.A. test does more harm than good has been unsettling and confusing.

Moscow Under Attack

By SERGEY KUZNETSOV

While political theories swirl, the bombings have reminded Muscovites that evil exists, and horror is right beside them.

Despite Madoff Guilty Plea, Questions Swirl and Rage Boils

NEW YORK, March 12 -- Some of Bernard L. Madoff's victims came to Lower Manhattan on Thursday to catch a glimpse of the man who had taken away their life savings, robbing them of their kids' college funds and of their pride.

Madoff Goes to Jail, But Questions Still Swirl

But his testimony was also shaped by his determination to shield his wife and family, The New York Times writes.

No sooner did the Treasury Department announce on Friday that it would increase its ownership in Citigroup than the questions began to swirl.

Go to Article from The New York Times»

Olympus Acquisitions Had Scant Histories

The three Japanese companies that are a focus of the controversy swirling around Olympus had no revenue and almost no business histories when the company started to invest in them in 2006.

Rumours swirl as China's Xi vanishes

Financial Times

Where is Xi Jinping? The man anointed to take the helm of the world's second-largest economy and most populous nation seems to have disappeared with just weeks to go before he is due to be officially elevated to lead the Chinese Communist Party.

See all stories on this topic »

Financial Times

Where is Xi Jinping? The man anointed to take the helm of the world's second-largest economy and most populous nation seems to have disappeared with just weeks to go before he is due to be officially elevated to lead the Chinese Communist Party.

See all stories on this topic »

mow

Line breaks: mow

Pronunciation: /məʊ /

verb

(past participle mowed or mown)Phrasal verbs

Derivatives

Origin

Old English māwan, of Germanic origin; related to Dutch maaien, German mähen 'mow', also to mead2.used to show that one thing happens immediately after another thing:

No sooner had I started mowing the lawn than it started raining.swirl

verb [I or T; usually + adverb or preposition]

to (cause to) move quickly with a twisting circular movement:

Swirl a little oil around the frying pan.

The fog swirled thickly around us.

swirl

noun [C]

The truck went by in a swirl of dust.

v., swirled, swirl·ing, swirls. v.intr.

- To move with a twisting or whirling motion; eddy.

- To be dizzy or disoriented.

- To be arranged in a spiral, whorl, or twist.

- To cause to move with a twisting or whirling motion. See synonyms at turn.

- To form into or arrange in a spiral, whorl, or twist.

- A whirling or eddying motion or mass: a swirl of white water.

- Something, such as a curl of hair, that coils, twists, or whirls.

- Whirling confusion or disorder: "high-pressure farce built around the swirl of mistaken identities" (Jay Carr).

[Middle English swyrl, eddy, probably of Low German or Scandinavian origin.]

swirly swirl'y adj.range

n.

- Extent of perception, knowledge, experience, or ability.

- The area or sphere in which an activity takes place.

- The full extent covered: within the range of possibilities.

- An amount or extent of variation: a wide price range.

- Music. The gamut of tones that a voice or instrument is capable of producing. Also called compass.

- The maximum extent or distance limiting operation, action, or effectiveness, as of a projectile, aircraft, radio signal, or sound.

- The maximum distance that can be covered by a vehicle with a specified payload before its fuel supply is exhausted.

- The distance between a projectile weapon and its target.

- A place equipped for practice in shooting at targets.

- Aerospace. A testing area at which rockets and missiles are launched and tracked.

- An extensive area of open land on which livestock wander and graze.

- The geographic region in which a plant or animal normally lives or grows.

- The act of wandering or roaming over a large area.

- Mathematics. The set of all values a given function may take on.

- Statistics. The difference or interval between the smallest and largest values in a frequency distribution.

- A class, rank, or order: The candidate had broad support from the lower ranges of the party.

- (Abbr. Ra.) An extended group or series, especially a row or chain of mountains.

- One of a series of double-faced bookcases in a library stack room.

- (Abbr. R) A north-south strip of townships, each six miles square, numbered east and west from a specified meridian in a U.S. public land survey.

- A stove with spaces for cooking a number of things at the same time.

v., boiled, boil·ing, boils. v.intr.

- To change from a liquid to a vapor by the application of heat: All the water boiled away and left the kettle dry.

- To reach the boiling point.

- To undergo the action of boiling, especially in being cooked.

- To be in a state of agitation; seethe: a river boiling over the rocks.

- To be stirred up or greatly excited: The mere idea made me boil.

- To vaporize (a liquid) by the application of heat.

- To heat to the boiling point.

- To cook or clean by boiling.

- To separate by evaporation in the process of boiling: boil the maple sap.

Muscovite

Muscoviten.

A native or resident of Moscow or Muscovy.

adj.

Of or relating to Moscow, Muscovy, or the Muscovites.

whorl

Line breaks: whorl

1.2Botany A set of leaves, flowers, or branchesspringing from the stem at the same level andencircling it.

1.3(In a flower) each of the sets of organs, especially the petals and sepals, arrangedconcentrically round the receptacle.

VERB

Origin

late middle english (denoting a small flywheel): apparently a variant of whirl, influenced by old englishwharve 'whorl of a spindle'.

1 則留言:

Google may soon launch Apple iTunes rival

Computerworld

By Sharon Gaudin Computerworld - Reports are swirling around the Internet that Google is in the advanced stages of testing a music service that could one day rival Apple iTunes. The latest reports the the company is internally testing the service, ...

張貼留言